Latest Posts

-

Four Historians Who Made the University of Reading

With our centenary fast approaching, David Stack looks back on four historians who played a crucial role in the foundation and development of the University of Reading. The One who got the ball rolling: Arthur Johnson (1845 -1927) The Revd… Continue reading

-

Vinegar Valentines: Loathing on Love’s Big Day

Dr Jacqui Turner explores the darker side of the divisive romantic celebration… Our association with Valentine’s Day is one of love and romance; however, considering St Valentine’s own grisly end, it is worth exploring a darker side, including some traditions… Continue reading

-

Breaking the Stained-Glass Ceiling: The Historic Appointment of Dame Sarah Mullally

On the 28th January, 2026 Dame Sarah Mullally will be confirmed as the Archbishop of Canterbury at St Paul’s Cathedral. Here, Dr Melanie Khuddro explores the significance of her historic appointment. Last year, The Church of England announced that the… Continue reading

-

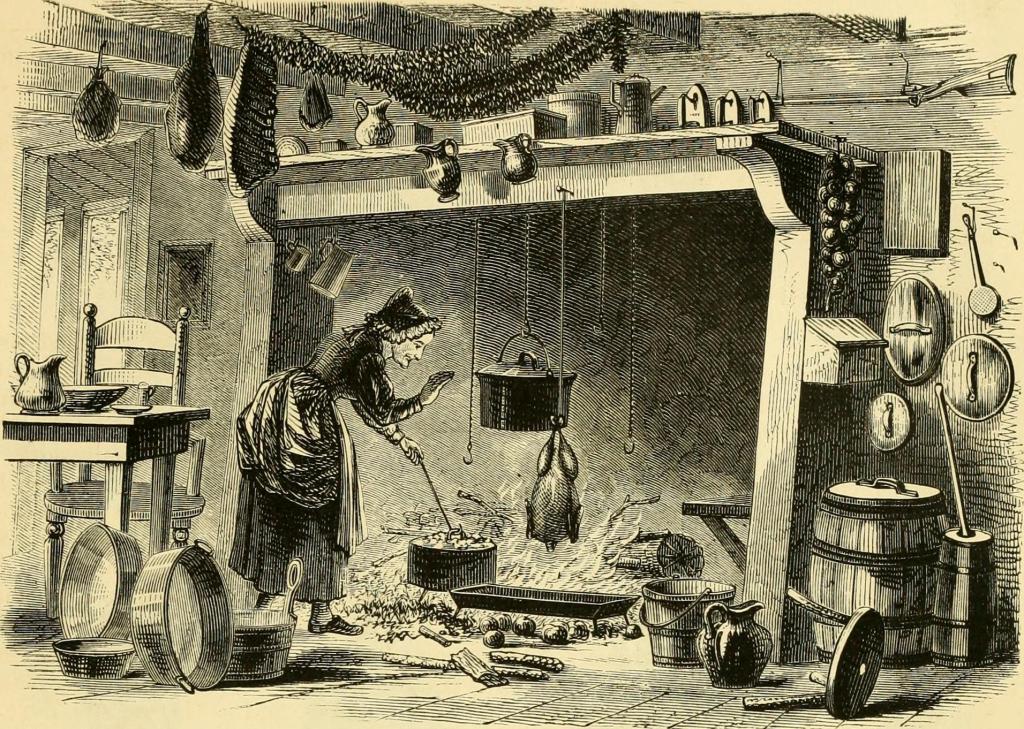

Homemade Georgian Winter Cheese

As part of their project working with the Royal Berkshire Archive (RBA) for the module HS2GPP: Going Public, Part 2 undergraduate students examined an 18th century cookbook. Today, Anna Puckey and Henry Merison share one of the seasonal recipes they found.… Continue reading

-

A Georgian Cookbook Mystery

As part of their project working with the Royal Berkshire Archive (RBA) for the module HS2GPP: Going Public, Part 2 undergraduate students Becky Storey and Eleanor Davis examined an 18th century cookbook. Read about the mysteries they uncovered below… Early… Continue reading