by Professor Anne Lawrence-Mathers

On Saturday 27 October, I had the privilege of giving a public lecture for the Friends of Reading Abbey, in the presence of the Mayor of Reading, Councillor Debs Edwards. The event took place in St James’ Church, sited amongst the ruins of the medieval abbey.

The lecture explored the relationships between medicine, magic, and miracles in medieval culture, using examples from surviving books and records from Reading Abbey. For my grand finale, I suggested that the abbey played an important role in spreading the Feast of All Souls in England, and in creating the later-medieval ‘season’ of Hallowmass (leading towards Halloween). It was exciting to talk about all this while standing beside an elaborately carved stone, which was probably part of the abbey church itself.

One of the most important records from the medieval abbey is a collection of miracle stories, which includes several dealing with ghosts and supernatural forces, as well as with the power of St James, whose hand was one of Reading’s most treasured relics. Perhaps most suitable for Halloween is the story of Alice, a girl from an Essex village who had a terrifying encounter in the early hours of Good Friday.

Alice went out to milk the family’s sheep while it was still dark, and was menaced by a phantom in the form of a dead man wearing a shroud. Alice was so scared that she fell into a fire, and her left arm was badly injured. Happily, the Hand of St James was able to heal Alice, even though other saints had failed her.

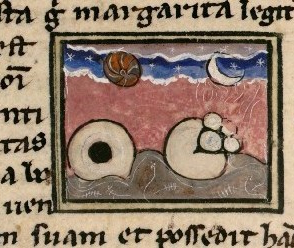

Less fortunate was Lady Aquilina, who endured an agonising four-day labour, despite all that midwives and doctors could do. King Henry II himself sent carefully-chosen gems and precious stones with special powers, from his own collection. These were placed on Aquilina, but to no avail. Was this a form of magic? The answer is that it was based on the belief that certain natural substances were imbued with occult qualities. Precious stones were therefore collected by the rich not just for their value, but also for their extraordinary healing powers.

However, the king’s jewels failed Aquilina and her baby – and she alone was saved from death at the last moment by the Hand of St James.

What links Reading Abbey more directly to the history of Halloween is its role in introducing the ‘new’ feast of All Souls into twelfth-century England. This feast was created by St Odilo, abbot of Cluny, the great French monastery to which Reading was linked. It was celebrated on 2 November, and called upon the living to gather and pray for the souls of all the dead, to save them from the power of the Devil. This put the living and the dead into a powerful relationship with one another – especially as All Souls took place the day after the feast of All Saints. This older festival, on 1 November, focused on the relics of the saintly dead, and on the spiritual power of the saints in heaven.

Reading Abbey’s royal connections gave it considerable influence in medieval England, and we know from its surviving service books that it celebrated the new, joint commemoration of All Saints and All Souls with great ceremony. Visitors were allowed into the abbey church, as well as into the church of St Laurence at the gate, at such special times. The event was marked by the ringing of bells and the lighting of special candles, including in night-time services. For extra emphasis, further services were held a week later.

The rituals now associated with Halloween have a complex relationship to this medieval Hallowmass. The older emphasis on attendance at special, night-time church services has been replaced by more secular activities. There are also no records of lanterns made from turnips or pumpkins being used in medieval churches! Even so, special contacts with the dead, feasting, lighting-up of the night, and communal protection against supernatural dangers all remain important activities at this time. If you go out trick-or-treating tonight – and especially if you do it in Reading – spare a moment to think about the medieval origins of these ideas.

You can find out more about Reading Abbey here.

You must be logged in to post a comment.