The storming of the Bastille was one of a series of unexpected events that led to the downfall of the Old Regime in France between May and August 1789. News from Versailles of popular minister Jacques Necker sacking had caused anxiety in Paris. The failed attempt by royal troops to seize control of strategic parts and buildings in the capital, such as the royal treasury, was the final act that caused the people of Paris to take up arms. At first glance, it may seem strange that a crowd was roaming the streets and buildings in search of weapons to protect themselves from the King’s army. However, since February 1787, the government had been facing growing resistance to reforms aimed at addressing a significant fiscal deficit, caused by France’s decision to support the independence of Britain’s American colonies.

This wasn’t the first time opposition to fiscal policies and the threat of bankruptcy arose due to the need to refinance war debts. In 1770, King Louis XV chose a partial default, and the following year, he eliminated legal opposition in the absolute monarchy, including judicial strikes, which paralyzed public action. Against this backdrop, his grandson’s reign stands out, as Louis XVI hoped to find other ways. However, he progressively lost control of the situation as his ministers failed to garner support for their policies. While hardliners accused the reforms of causing disorder and called for the enforcement of tradition and authority, Louis XVI was caught between the official discourse presenting him as a benevolent ruler and the public’s demand to address their grievances through their representatives in a meeting of the Estates General.

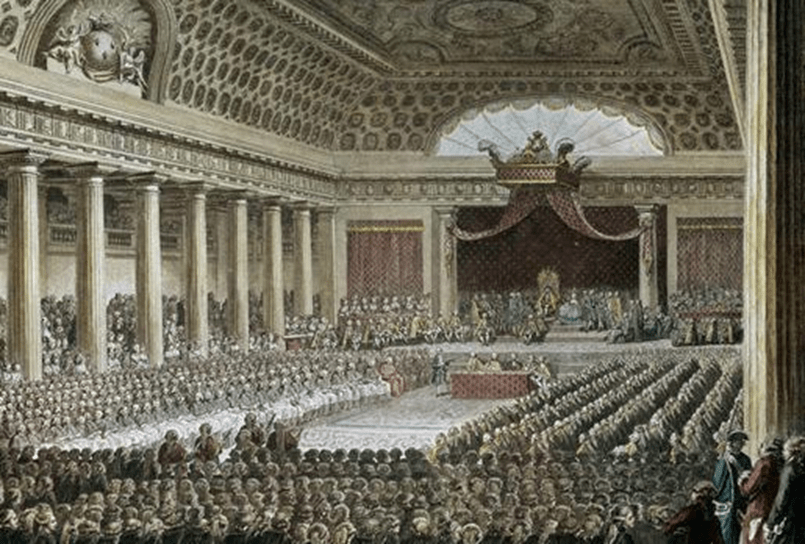

The decision to convene this medieval representative institution itself challenged the absolute authority of the king. The Bourbon rulers hadn’t called the Estates General since 1615. However, in August 1788, the looming bankruptcy left Louis XVI with no other choice. As the king feared, the decision generated new problems, and details pertaining the organizing of the Estates General transformed a political crisis into a social conflict. While the French were united in their dissatisfaction with ministerial policies and their desire to reform institutions, the Estates General proved inadequate. Traditionally, the elected deputies didn’t represent the population as a whole but rather each of the three estates: the clergy, the nobility, and the third estate (the rest of the population). As soon as the Estates General opened on May 6, the deadlock between Louis XVI’s government and the people shifted from a struggle for freedom to a conflict between the deputies of the nobility and the third estate, fighting now for equality. For six weeks, the Estates General were paralyzed as the nobility rejected repeated invitations from the third estate to sit and deliberate together in a common room. Ministerial attempts at reconciliation failed, leading the deputies of the Third Estate to proclaim themselves as the National Assembly, claiming to represent 94% of the nation.

The march on the Bastille was the response of the people of Paris to Louis XVI’s third attempt to suppress the principle of national sovereignty, which he reluctantly conceded on 23rd June. While public buildings were investigated in various parts of Paris in search for weapons, groups of individuals gathered at the medieval fortress. The Bastille, which had been converted into a state prison, was also targeted as a symbol of ministerial tyranny. Although it housed only a few inmates, they were notoriously arrested through sealed letters issued by ministers, either for security reasons or upon private requests from families worried about the morality of relatives. Other symbols of coercion were also attacked on 14th July. The entrances to the wall being constructed around the capital city to prevent fraud and collect taxes on goods entering the capital city were targeted, looted, burned, and destroyed. Paris spiralled out of control as royal authority collapsed. Soldiers of the Gardes Françaises, troops responsible for Paris’ security joined the attackers of the Bastille. The municipality attempted to restore order, and protect people and property by creating the new Garde Nationale. However, they were powerless to prevent the beheading of the governor of the Bastille, as well as the execution of the intendant of Paris and his nephew who visited Paris a week later.

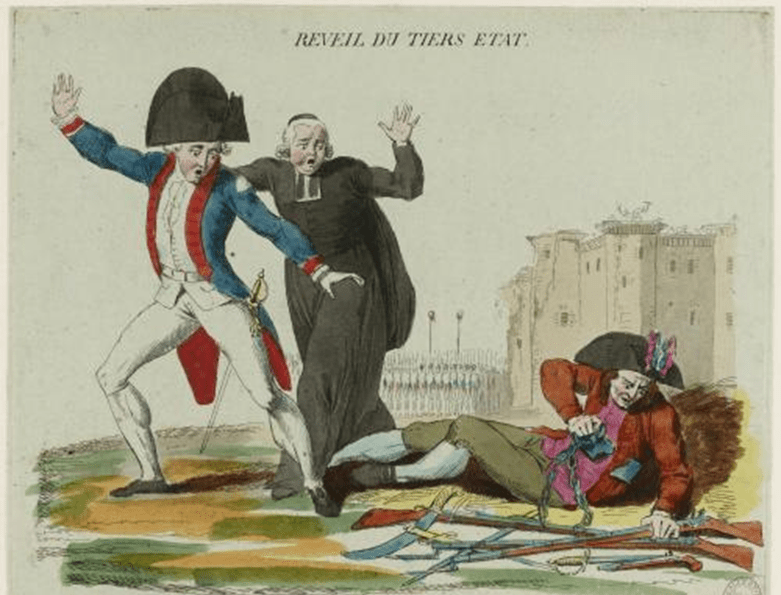

Image 1: Awakening of the Third Estate: two members of the nobility and the clergy are scared by the awakening of the third estate, or the people of Paris taking up arms. At the back the Bastille and a crowd carrying the head of the governor of the Bastille and his deputy.

Image 2: Storming of one of the Parisian octrois (tolls) built by the architect Ledoux.

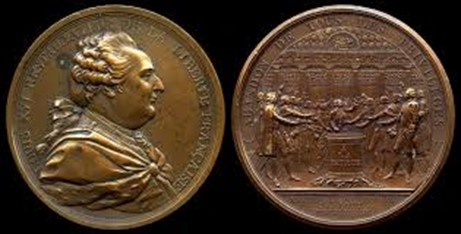

While the specific objectives of Louis XVI’s ministerial reshuffling are unknown, fears of a royal coup solidified the political and social revolution imposed by the deputies of the Third Estate in Versailles. Over the next two weeks, the authority of royal agents and institutions crumbled throughout the kingdom, paving the way for the creation of new institutions and social relationships based on the principles of liberty, equality, property, and resistance to oppression. These new principles embodied the spirit of the extraordinary events of 1789 that brought down a monarchy and a regime that boasted about the love and obedience of its subjects to their King. Against all odds, Louis XVI was hailed as the restorer of liberties and medals struck to celebrate the union of the French with their monarch, and the abolition of privileges. However, a new ruler emerged on Bastille day: the people of Paris, both as an actor and as a concept in service of the revolution and its social and political goals.

Image 1: A medal of King Louis XVI hailed the restorer of liberties; on the reverse, depiction of the night of August 4. when deputies of the nobility and clergy solemnly surrendered their privileges with the purpose of appeasing the revolts that spread across the countryside in the aftermath of the storming of the Bastille.

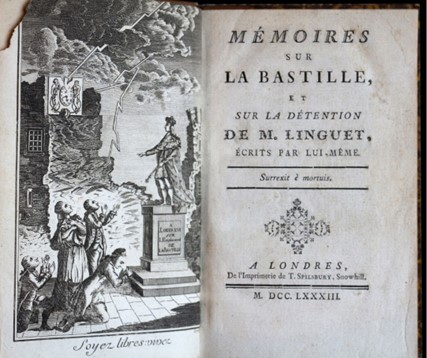

Image 2: Lawyer Linguet contributed to spreading the bleak picture of the state jail in the pamphlet he published about his stay in 1783. The engraving represents subjects of Louis XVI praising and thanking the king for the (recommended) destruction of the Bastille. Louis XIV enjoyed reading Linguet’s work but the controversial and satirical lawyer, who recommended bankruptcy in 1788, was nonetheless sent to the Bastille under his reign.

Prof Joël Félix is professor of History at the University of Reading, specialising in the Ancien Regime and French Revolution, particularly fiscal issues in the wider European context.

All comments and opinions presented in this article are that of the author.

We have made every effort to abide by UK copyright law but in the instance of any mislabelling of images, please contact the author of the blog post

You must be logged in to post a comment.