If you enjoyed our piece in The Conversation this month and would like to hear more, here is the long read which also includes a little more history and things not to do …

Leisure is an essential component of modern life but reflecting on leisure and pastimes is a means of capturing the cultural and emotional ‘feeling’ of a time but can also tell us a great deal about intellectual beliefs which often influence historical events. Leisure is often associated with festive culture and rites of passage. It is a dynamic blend of local and national culture across all the constituent parts of the British Isles and beyond. As such, histories of leisure incorporate themes such as identity and class alongside a sense of place and time.

Throughout the Victorian and Edwardian periods, leisure flourished as people had more free time and legislation was passed limiting the length of the working day and working week. The eight-hour day was introduced to a series of individual (often manual or physical) industries – from 1901 for factory workers, 1908 for mine workers and 1912 for shop and retail workers. In response to the shorter working week, seaside towns sprang up at the end of railway lines making time away accessible for the working class.

There was also time for the most ordinary of pastimes. Going for a walk: whether it was Dickens striding the streets of London after dark, Darwin shuffling along his ‘thinking path’ after lunch, or Wordsworth wandering amidst his ‘host of daffodils’, the Victorians couldn’t stop putting one foot in front of the other. Or finding time to protest. We tend to think of the Victorians as staid and compliant but nothing could be further from the truth. It wasn’t Just Stop Oil who invented the modern protest: Corn Laws, Charters, Rational Dress, the Vote, foreign wars, low pay, you name it and the Victorians protested about it. To such an extent that we might legitimately judge it a form of leisure.

If you’re struggling to know how to spend the last of your free time as summer draws to a close, take a leaf out of the Victorians’ book, with these strangely fun leisure pursuits.

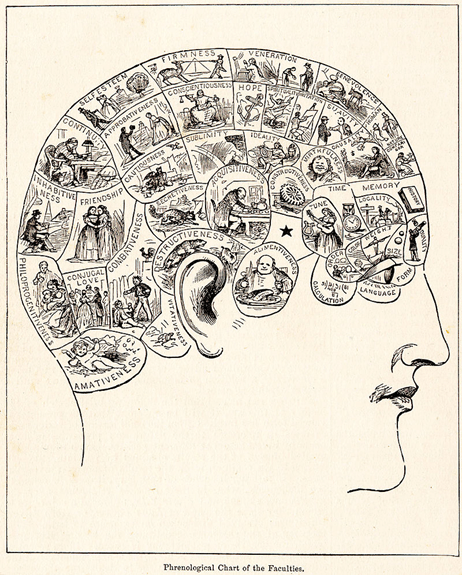

1. Read the bumps on your head

Put you hand above your right ear. Do you feel a bump? Then you are clearly selfish!

Partly in response to the growth of the new cities, packed full of strangers, and partly out of a desire to better understand themselves, the Victorians embraced the idea that character could be read from one’s outward appearance, especially one’s skull shape.

Phrenology was the pseudo-science of reading the bumps on a person’s head to determine their character and potential shortcomings popular across Europe and the US. Arguably, the most influential theorist and practitioner was George Combe who wrote Constitution of Man in 1828 explaining his ideas of human development through inherited mental characteristics decades before the publication of Charles Darwin’s Origin of Species in 1859. Combe’s work was so influential that Queen Victoria consulted him to try to understand why her son Albert Edward or ‘Bertie’ (later Edward VII) lacked the intelligence and practical application of his older sister Victoria.

If you want to undertake your own phrenological reading – or, better still, do one for a friend – all you will need are your fingers; a phrenological chart or bust, identifying the location of the various organs of the brain; and a willingness to interpret evidence imaginatively! If you are in a hurry, you can divide the skull into three, with the organs of intelligence clustered at the front; organs of morality on top; and the animal organs clustered, low down at the back.

A friend with an unusually high forehead is likely to be intelligent, but one with a particularly thick neck might be best avoided.

Phrenological diagrams by Coombe can be seen at the British Library Phrenological diagrams by George Combe | The British Library (bl.uk) To read more about Coombe, his world and what it can tell us about the Victorians you can also read David Stack’s Queen Victoria’s Skull: George Combe and the Mid-Victorian Mind (2008).

2. Be romantic and create a love token

Love tokens in the Victorian era were synonymous with emotion. Generally, a love token was a round flat disc (often smoothed coins), engraved by hand with names or initials intertwined. You can see a collection at the Museum of London Crafted love: bent coins, lovespoons and a whale’s tooth! | Museum of London

It wouldn’t be possible to discuss love tokens without referencing St Valentine’s Day though at the end of the C19th not all cards were as you might expect. A fashion for cruel or spiteful cards flourished which were cheaper and less ornate than their romantic counterparts. They included caricatures of women containing mocking sentiments that most often related to a woman’s appearance or less than feminine characteristics.

Prisoners sentenced to transportation to Australia often made love tokens for those they were forcibly separated from, and the Foundling Museum, built on the site of the Foundling Hospital to care for abandoned babies, houses a collection of tokens left by heartbroken mothers. They were often tiny and, on the surface, insignificant, from coins and simple buttons to half a hazelnut shell — but they were symbols of devotion and desperation. Homepage – Foundling Museum.

To make the simplest form of love token, you will need a coin, a hammer, and a vice. Put the coin in the vice, leaving about one third on view, and hit it with the hammer! Once it has bent, flip the coin over, leaving the unbent third showing, and now hit that with the hammer. Done! You have a gift for your loved one to cherish!

If you are looking to buy a Victorian love token take care, some love tokens were made after death and were often crafted from the deceased’s hair!

3. The Sporting Life: Kick someone’s shins

Welly-wanging, bog snorkelling, cheese rolling, wife carrying, worm charming and shin kicking all have their origins in the nineteenth century and before. But if you enjoyed striking the coin or discovered a highly developed organ of combativeness during your phrenological examination, you might also want to try England’s oldest martial art – shin-kicking.

The roots of this strangely violent sport are believed to lie with Cornish miners in the 17th century, but in the nineteenth century it became popular in Lancashire mill towns, where it was known as clog-fighting or purring. Participants don shepherds’ smocks, hold each other by the shoulders, and take turns to connect their foot with their opponent’s shin. The contest is won when one competitor cries ‘Sufficient’, to indicate that they have had enough of being kicked!

But the Victorians also played a great deal of organised sports. Although there has been sport and sporting events since ancient times, the Victorians, in their inimitable manner, imposed codified or consistent rules on sports to ensure gentlemanly conduct and fair play. From boyhood the lives of upper and middle class men were fiercely competitive and boys were expected to excel on the sports field as well as academically and in business. In 1863 the Football Association (or FA) was formed and in 1871 the Rugby Football Union followed suit. The new codified games were also suited to working class life in industrial cities as they needed only limited time and space and as such their popularity spread rapidly. The current Everton Football Club was originally a Methodist Sunday School team and began life as St. Domingo Church Sunday School in 1871.

Women’s sports were consistently more genteel and to a great extent hampered by ideas of female modesty and clothing. But for women, the most significant pastime came with the invention of the bicycle. While it may seem ordinary today, the introduction of the bicycle was a revolution for women’s independence and influenced a radical change in women’s clothing. While men were concerned that a woman straddling a bicycle seat would lead to sexual arousal, for women the opportunity to exercise and travel led to a new feeling of empowerment and self-reliance. It also led to a reconsideration of the practicality or impracticality of their clothing leading to a new movement for rational dress. Find out more about women and cycling at the British Library The ride for independence: Victorian ladies cycling fashion | The British Library (bl.uk) Find out more about the Society for Rational Dress, established in London in 1881, which understood restrictive clothing as indicative of restrictions on women’s lives The Rational Dress Society’s Gazette | The British Library (bl.uk)

4. Fake a photograph or make a stereoscopic image

In our age of routine photographic enhancement, it would be easy to consider photographic fakery a modern phenomenon. But it isn’t, it is as old as photography.

The most famous fakes were a series of five images created by two young women in 1917. Elsie Wright and Frances Griffiths’ fakes became known as the Cottingley Fairies and depicted both girls with fairies at the bottom of their garden. While there was some contemporary debate over their authenticity, the images fooled many of the great and the good worldwide including Arthur Conan Doyle. Elsie and Frances only admitted that they were fakes in the 1980s.

Most people know that the Victorians pioneered photography, but fewer are aware that they also invented 3D technology. Stereoscopy – the technique for creating the illusion of depth in a two-dimensional image – was discovered by Charles Wheatstone in 1832 and popularised by him in the mid-nineteenth century. Stereoscopic image cards of landscapes, buildings, and portraits remained fashionable throughout the nineteenth century, and you too can easily make your own stereoscopic images. What Wheatstone realised is that our sense of depth is created by the distance (c.63mm) between the pupils of our left and right eyes, which means each sees a slightly different image, which our brain then aligns. To create this artificially, – the stereoscopic effect – all one need do is to take two photographs of the same object, from very slightly different positions, place them side-by-side, and then look at them cross-eyed. This cross-eyed viewing can be achieved with practice, but many middle-class Victorian homes had stereoscopic viewers, which worked in the same way as the Fisher-Price View-Master toy which older readers (and the authors!) will remember from the 1970s. Alternatively, a modern stereoscopic viewer (improbably designed by legendary Queen guitarist Brian May!) can be purchased or, for the ultimate hack, it is even possible to download an app that will help you create 3D images on your Smartphones.

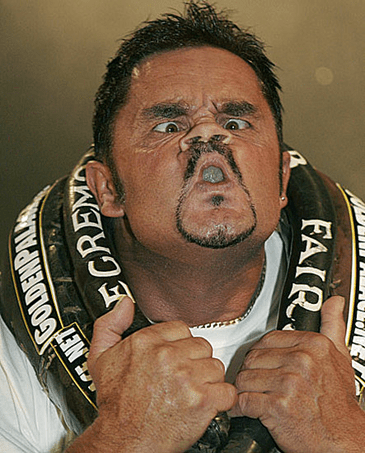

5. Gurn

Alongside phrenology, many Victorians became interested in physiognomy, which took facial features as an indication of character. This pseudoscience almost scuppered the most important discovery of the nineteenth century. In 1831, when Captain Robert Fitzroy of HMS Beagle interviewed a young naturalist by the name of Charles Darwin to accompany him on his voyage around the world, his first impression was not favourable, concluding that “no man with such a nose could have energy”. Fortunately for Darwin “his brow saved him”, for us too as his experiences on that voyage laid the basis for his theory of evolution by natural selection.

One pastime you can indulge in, which will simultaneously subvert any attempt to read your physiognomy, is the rural tradition of gurning. The word refers to practice of deliberately distorting your facial expression by projecting your lower jaw forward and up. (If Darwin had been a skilled gurner he would have been able to cover that troublesome nose.)

In the tradition, which dates to at least the thirteenth century, gurners frame their face in a horse collar. Anyone can do it, although it would be ill-advised to gurn when presenting your love token.

Wellcome Trust have drawings that compare human features to those of animals and what this tells us about individual character Drawing the human animal | Wellcome Collection

- Things NOT to do!

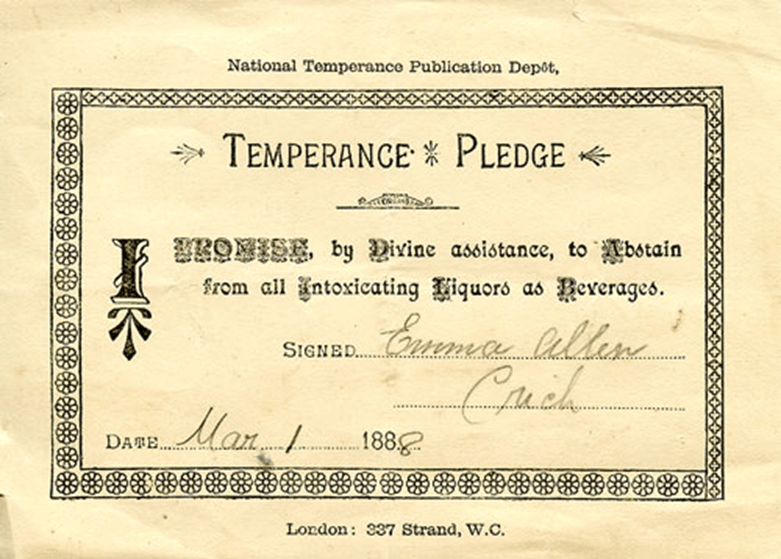

Drink alcohol: Dry January may be a challenge today but temperance or abstinence from drink is a constant and contentious historical phenomenon. In the US it led to Prohibition between 1920 and 1933. In the UK the temperance movement campaigned to abstain or limit alcohol particularly among the working classes. Participants were encouraged to sign ‘the pledge’ which encouraged teetotalism from the 1840s onwards. Would you sign the pledge? Even just for January?

American born Nancy Astor, the first woman to take her seat in the British parliament, was teetotal and caused something of a panic when she introduced the Intoxicating Liquor Bill in 1923. Her American birth meant that many thought she was trying to introduce prohibition to the UK. This was the first bill introduced by a woman and it was to limit alcohol consumption and raise the legal age for drinking alcohol. It is the reason why, in the UK, we must wait until age 18 to drink today.

Either shave or cultivate your facial hair very carefully: For Victorian and Edwardians, male shaving was a ritual and for some a luxury. The upper classes would regularly visit their barber for a shave which was as common as having a haircut. Tourist guides indicated the best establishments to visit. Less affluent men took extra care when shaving as the tool of use was a self-sharpening ‘cutthroat’ blade and cold water, possibly the reason that so many Victorian men had beards! The modern double edged wet shaver was introduced in the early twentieth century but the most significant change came in 1895 when King Gillette invented disposable razor blades.

A revival of the beard was popularised by the military and explorers who were unable to shave regularly. As such, the beard became a sign of manliness, adventure and virility. However, care needed to be taken the facial hair was of the right type – male facial hair again, indicated character and ‘Character Reading by the Moustache’ made it into Boys Own Annuals. Avoid a thin, pencil moustache as it indicates ‘sharpness and cunning, very dangerous’ while you may more safely consider a tidy, medium moustache following the upper lip which indicates ‘practical common sense’ and ‘shows an aptitude for business’.

For women, shaving body hair did not gain any traction until the 1920s when clothing became less restrictive and bodies less covered.

Dr Jacqui Turner is Associate Professor of Modern British Political History at the University of Reading, specialising in 19th and early 20th century parliamentary politics and political cultures.

Prof David Stack is a Professor of History at the University of Reading, specialising in the inter-relationship of ideas and politics in the history of Britain and beyond.

All comments and opinions presented in this article are that of the author.

We have made every effort to abide by UK copyright law but in the instance of any mislabelling of images, please contact the author of the blog post

You must be logged in to post a comment.