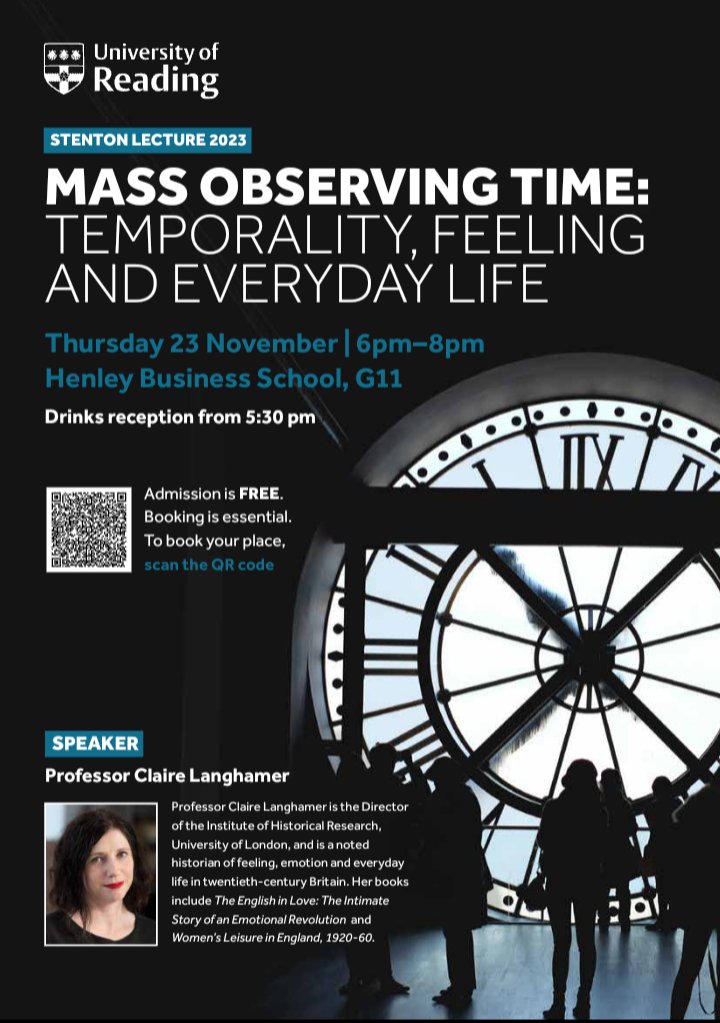

Mass-Observing: Time, Temporality and Feeling in Everyday Life.

Presenter: Professor Claire Langhamer, Director of the Institute of Historical Research.

Having on several occasions during my undergraduate degree been directed to the Mass-Observation database for source material, I was looking forward to learning more about it. Claire introduced the topic with a fascinating selection of extracts from the Covid diaries requested by Mass-Observation at the start of the pandemic lockdown in March 2020. She used this period of profound crisis as a reference point for her theme of how ordinary people experience time. The extracts provided a reminder for me and, I’m sure, the whole audience of how, in that unusual period, time moved at a much slower pace than in normal times. She developed her theme by exploring the differing ways people might experience time.

She reviewed the history of the Mass-Observation project which was formed in 1937 by three young men seeking to create a history of the everyday lives of ordinary people. Through thousands of voluntary contributors, it collected material either through diaries, or questionnaires sent for special projects. These were then edited and published in a series of books and special reports. Of particular note were the contributions collected during the Second World War. An example of a special project was a ‘mood chart’ created in 1944 reflecting how happy or unhappy people were feeling during a fixed period. The operations of the Mass-Observation project stopped in 1960 but were revived in 1981 by which time the organisation was under the wing of the University of Sussex and the Archive had been opened up as a public resource.

She explained that in recent years the Mass-Observation project has had several initiatives in addition to the Covid diaries, notably an invitation of older participants to write a letter to their 16-year-old self in 2015 and a survey of activities on a single day in 2017. In 2008 participants were asked to construct a lifeline of their entire lives showing the highlights and low times. Claire showed a wide selection of these which dealt with time in intriguingly different ways, and with varying interpretation of events. (Of particular interest to the audience were how these dealt with the question of sexual activities.)

Claire concluded by expressing the view that in the ‘temporal turn’ historians needed to spend more time with time. Here the Mass-Observation project is a valuable source by illustrating how time is experienced by people. Of significant value is the ability to review the contributions of single individuals over time, and there remains much valuable research that can be done with the Mass-Observation archives.

There were many interesting questions, and too many to record here. The one that sticks in the mind was the final one which postulated the proposition that if Mass-Observation is taken to its logical conclusion will society need historians at all? (The audience gasped.) But Claire set everybody’s mind at rest by emphasising that only historians have the skills to be able to interpret and communicate the results of Mass-Observation data.

John Jenkins is currently studying for an MA in History at the University of Reading.

2 responses to “Reflections on the Stenton Lecture – by John Jenkins”

[…] as our wonderful Stenton lecture last month showed, time is by no means fixed and immutable. It speeds up and slows down and is […]

[…] as our wonderful Stenton lecture last month showed, time is by no means fixed and immutable. It speeds up and slows down and is […]