May Hobbs was born in Hoxton, East London in 1938. Like many other working class women, by the 1960s she found work as a nightcleaner in the ever-increasing number of high-rise office blocks in central London. Much of this work was organised through contractors, the offices outsourcing their cleaning requirements to the cheapest company who would then hire the women to clean the offices from ‘10pm till 6am, five days a week’.[1] Around ’70 per cent of the [cleaning] work-force were part-time females’ with young families who maintained the home throughout the day, and did this work at night.[2] A large proportion of the workers were also from ethnic minority groups, whose language barriers and lack of support from the government compelled them to accept the low pay and anti-social hours of nightcleaning.

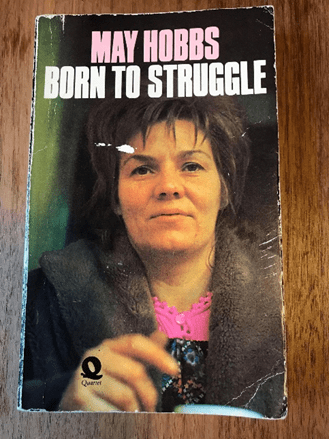

May Hobbs’ Book, Born To Struggle, published in 1973

In 1964, the cleaning contractors were paying the nightcleaners £9 a week, and as Hobbs stated, ‘though we realised we were being exploited – by that I mean used to make money for the contractors – and moaned on about it, we never really did anything to change things’.[1] It was not just their wages though that were problematic; working conditions for the nightcleaners also became a key issue. In the winter, the heating was turned off, and [the buildings were] humid and hot in the summer. Some cleaners even complained that they were locked in their buildings through the working hours’, and thus unable to leave until their shift had ended.[2] The nightcleaners were thus aware of their position – making money for the contractors whilst receiving very little of the economic benefit from working long, anti-social hours in poor conditions. From this awareness, Hobbs began to organise the nightcleaners, imploring trade unions to support their struggle against these contractors, and asking the Women’s Liberation Movement in Britain (BWLM) to assist in their organisation.

Hobbs formed the Cleaners Action Group (CAG) in the early 1970s and demanded £18.75 per week wages, sick pay, two weeks’ notice of contract termination, holiday pay, adequate staffing on all buildings, adequate cover money, and recognition of the union.[3] Hobbs had already begun unionising the nightcleaners by encouraging all the women she worked with to become members of the Transport and General Workers Union (TGWU). This was not the total solution though, as the union was unwilling to acknowledge the women nightcleaners’ demands, and argued that women workers were instead earning ‘pin money’, and only employed temporarily. May Hobbs’ unionisation thus began a bigger struggle to get women workers and nightcleaners recognised as important union members.

The British Women’s Liberation Movement also got involved with the campaign along with many women on the left, who assisted in printing leaflets, talking to nightcleaners at the beginning or end of their shift to encourage trade union membership, and supporting the broader organisation of the CAG. Most significantly, the BWLM became ‘intermediaries – putting cleaners in touch with the Union, because we were the people who had the time’, and were thus able to make connections between the trade unions that May Hobbs was attempting to organise the nightcleaners into, and the CAG themselves.[1] This notion of the BWLM having the time to organise with the union demonstrates the distinctively working-class nature of the nightcleaners dispute, as those who were being organised, the nightcleaners themselves, did not have the time to contact the trade unions that could have helped their campaign. Instead, it was the more middle-class dominated, though not exclusive, BWLM who could spend time forging these union connections, and contribute their own experiences of organisation to the CAG.

Empress State Building, Fulham, London

The most significant event for May Hobbs and the CAG was at the end of July 1972 when ten cleaners came out of the twenty-six-story-high Ministry of Defence building, the Empress State Building, in Fulham.[2] This strike, which lasted until 16th August, involved the CAG and Women’s Liberation who ‘set up round-the-clock pickets’ and which spread considerably among nightcleaners as more women came out in sympathy strikes for those at the Empress State Building.[3] On 6th August ‘twenty women in the Old Admiralty building in Whitehall also joining in…the GPO engineers stopped servicing their telephones, the dustmen left their bins full’, and on 13th August ‘twenty more came out the Home Office’s Horseferry Road annex’.[4] These acts of solidarity drew heavily on trade union beliefs in working-class organisation and camaraderie, and allowed the CAG to showcase the plight of nightcleaners across London on a scale that had previously never been seen, whilst also having considerable support from other TGWU members.

May Hobbs and the Cleaners Action Group organised for the improvement of conditions for nightcleaners, some of the most exploited workers in London; blue-collar workers cleaning white-collar workers’ offices. Hobbs’ determination to organise through the trade union, combined with the grassroots approach to recruitment, demonstrated her commitment to the working-class ideals of solidarity for collective progress. Despite not being entirely successful in their demands, primarily due to the contract-based and dispersed nature of nightcleaning, Hobbs and the CAG challenged the TGWU’s male-centric outlook and, with the help of the BWLM, made sure ‘people know a bit more about what went on in their offices, while they were snugly tucked in their beds, to keep things nice and civilised for them when they got in for work’.[5]

Amy Longmuir is a PhD researcher and Associate Lecturer in the Department of History. This research is funded by the AHRC through the SWWDTP.

[1] C. Cockburn, ‘NIGHT CLEANING’, Socialist-Feminism and Nightcleaners, Sally Alexander Papers (quoting Sally Alexander).

[2] Ibid., p.84. See also: Alexander, ‘The Nightcleaners’, Red Rag, 6,p.5.

[3] Hobbs, Born to Struggle, (London, 1973), p.84.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid., p.85.

[1] Ibid.

[2] Sullivan, Brush Off, Low Pay Unit, 1977, Socialist Feminism and Nightcleaners, Papers of Sally Alexander, p.18.

[3] S. Alexander, ‘The Nightcleaners, Red Rag, 6, p.2.

[1] Ibid., p.63.

[2] J. Sullivan, Brush Off, Low Pay Unit, 1977, Socialist-Feminism and Nightcleaners, London, LSE Women’s Library, Papers of Sally Alexander, Women and Work, 7SAA/5.

You must be logged in to post a comment.