The artist Polyp began drawing political cartoons over forty years ago, while still a student. After a period as a care worker, he got his big break producing searing satirical cartoons for the New Internationalist magazine. Alongside a growing body of illustrated works of history, Polyp continues to campaign and produce satirical cartoons- and build props: a larger than life puppet of ‘Tom Paine’s Bones’ is in progress right now for a freethinking festival. He is also chair of the Peterloo Memorial Campaign in Manchester.

Back in June 2024 he was interviewed by Professor David Stack.

DS: You’ve enjoyed a diverse career, drawing everything from political cartoons to illustrating children’s books. Where does your interest in history fit into your wider work?

Polyp: My first book, which I produced for Friends of the Earth International, was a global history called Speechless, based around the idea – which was very popular at that time – of what would the world look like if it consisted of just 100 people. And I wanted to draw this miniature world and play history out from the Stone Age. My second book was a more straightforward history of the co-operative movement, with which I am very involved here in Manchester. Then I started to drift towards stuff that people didn’t want to talk about, like Peterloo. I don’t really have an interest in history in the way that some collectors do. I’m not interested in it as a hobby, for me it’s more a political thing.

DS: So you’re very much not an antiquarian?

Polyp: Is that the term? No, don’t collect stamps either! For me it’s political. So many people are so contemptuous of democracy now that part of me wants to remind them of the immense costs that went into getting the vote and that it is something special that you can replace the government without violence. With my Peterloo book I wanted to bring that forgotten history back to life, but also to explore the political challenges that these amazing, shocking incidents bring up for us today. You know history needs to be about the present as far as I’m concerned. What’s that slogan? If you forget the past you are doomed to repeat it.

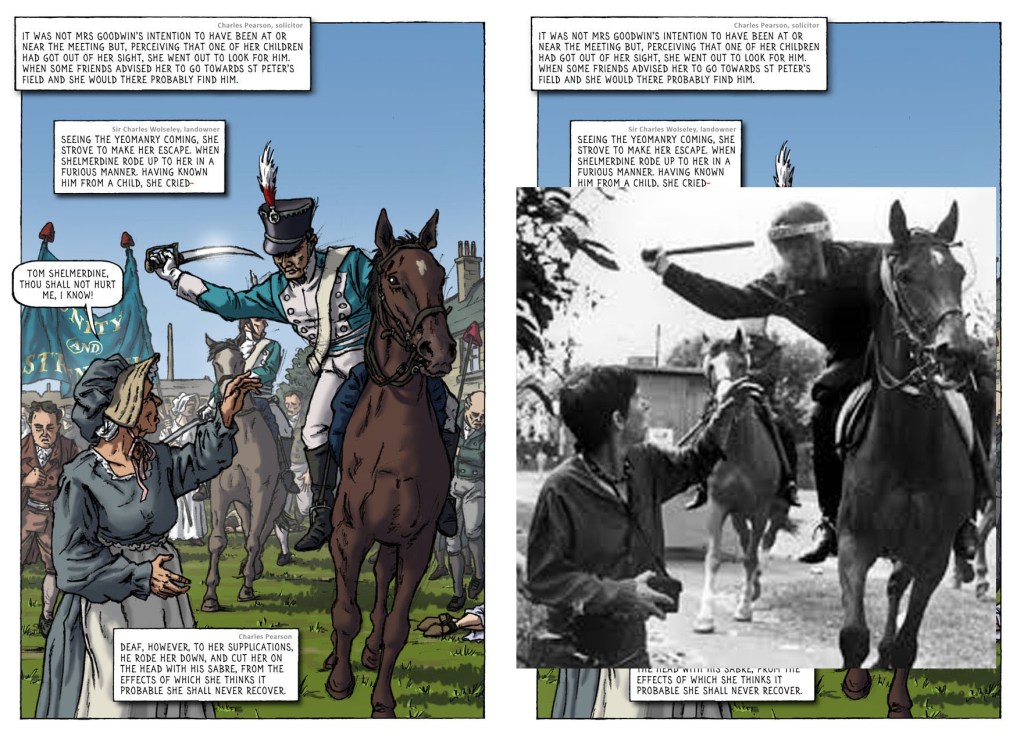

DS: One thing I really like about your work is the way in which your images always sit alongside verbatim quotes from the period.

Polyp: It is interesting the way that people fictionalise a particular piece of history say like HBO’s Rome – I thought that was really, really interesting. It achieved a lot of things, but I don’t think anybody thought it was literally true. It was structured in such a way you could tell it wasn’t supposed to be like stuff that was from the records. So sometimes it’s OK to fictionalise. But other times it can slip over into arrogance to assume that you have the right to edit history in order to reinforce your own political beliefs and spread them to others. I don’t think that’s acceptable.

DS: So you want to produce a history that is more true to the record …?

POLYP: As I say, there are exceptions. What Arthur Miller did with The Crucible and the changes he made there to the historical record to make a particular point about the way in which people think, and how polarised political and religious incidents can impact on people’s lives, and the metaphor with McCarthyism – that was interesting. But mostly it is arrogant to think you have the right to edit history – either for political purposes, or to sanitise it. And why sanitise history? Why not make it warts and all? You’re completely patronising the audience if you think that they don’t have the capacity to distinguish and work out for themselves who the hero is, or that they need their heroes polished to perfection in order to have any faith in them. That’s just nonsense. You should trust the intelligence of your audience to be able to handle ethical and moral complexity.

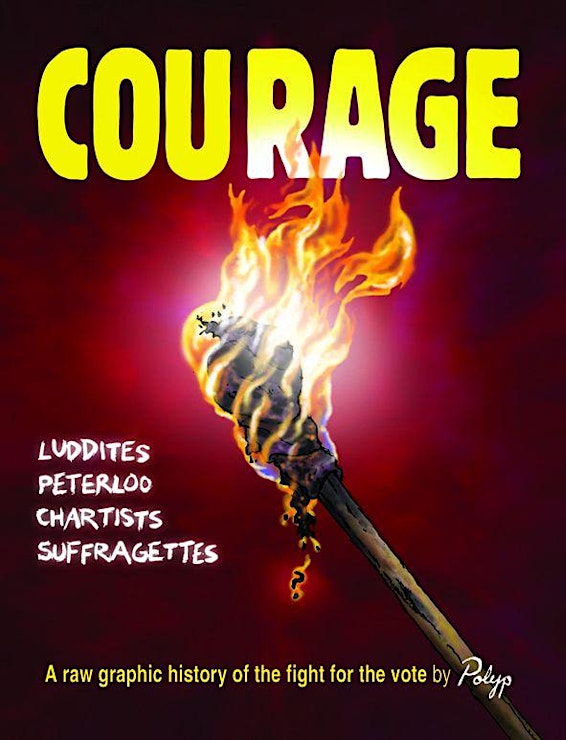

DS: Your new book, which brings together the stories of the Luddites, Peterloo, the Chartists, and the Suffragettes, is called COURAGE. Why that title?

POLYP: I wanted an emotionally provocative word which helped to capture story of democracy as a fight, as a struggle, with people demanding rights, demanding democracy and struggling – which isn’t always the way it is told. But there’s also a bit of a hidden pun in the title, it’ll be interesting to see who spots it!

DS: What did you learn in putting the book together?

POLYP: Putting together the Luddite chapter I realised the extent to which we’ve been sold a relatively sanitised popular image of them. With the Suffragettes I was struck by the moral complexity involved in the fight for democracy. And I thought it was important to explore that moral complexity, even if it made readers uncomfortable, rather than give some Soviet propaganda style heroic tale of simple virtue.

DS: Do you mean in terms of direct action?

POLYP: Yes, I wanted to avoid some of the cliches. Absolutely their direct action was justified, but at the same time not every action the Suffragettes took was always reasonable, and innocent members of the public were sometimes the target. You know, setting fire to post boxes is one thing, but spilling a vial of acid on a postman’s hands? Or placing bombs in crowded railway stations? That’s at a different level to the way most of us think about direct action or political violence around the world. I spent some time thinking about how to handle that aspect.

DS: I am struck by the restraint and realism in your books.

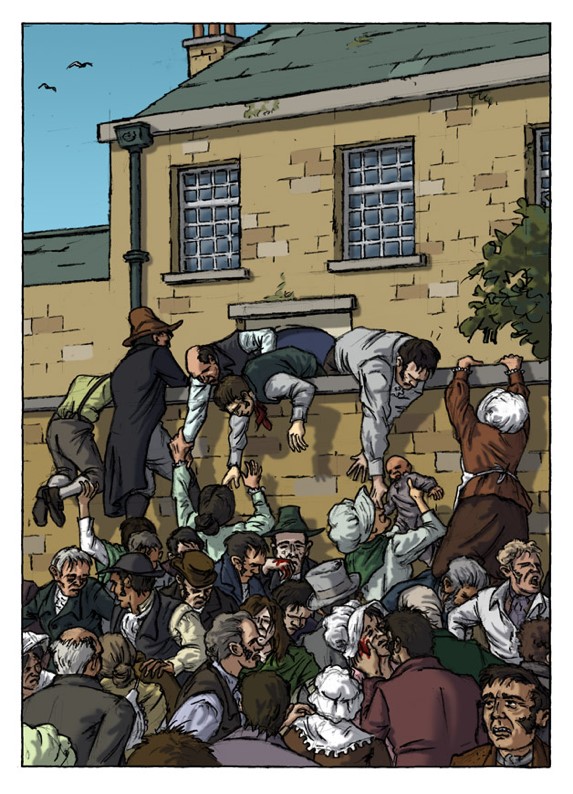

Polyp: A lot of comic book drawing has a tendency to melodrama and to glory in a pornography of violence. I try to avoid those extremes. The force-feeding scene in the suffragette chapter is obviously violent but it gets a lot of its power from the restraint on the other pages around it. And when I draw people in extreme situations, I try to avoid theatricality. I will often go back to real contemporary images and let them inspire my historical ones. One of my Peterloo images of a protestor being attacked is based on a famous photograph from Orgreave during the miner’s strike in 1984. Another one, depicting the Peterloo protesters trying to escape by climbing a wall, is based on a famous photograph of football fans escaping the Hillsborough disaster. I think both the physical realism and the resonance this creates with later struggles is important.

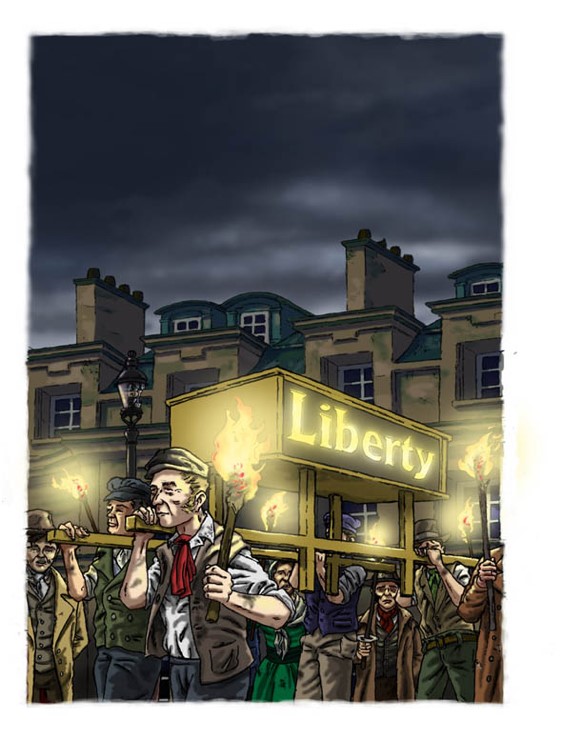

DS: Let’s talk a bit about Chartism.

Polyp: I see Malcolm’s book on your shelf. I slightly cursed him when I was using his material for the Chartist chapter because he described this torchlit procession in which a group were carrying a box illuminated from inside with the word Liberty on the side in glass, and I’m like, ‘Right, I’m drawing that’ but then when I went through the description I was trying to work out what this object must have looked like, and I couldn’t quite picture it. And so, because I’m a prop builder, I decided I’d build it in my head! And that was tough! The description was quite sparse and working out how this thing could possibly have been carried, without keeling over, was intriguing. I hope I got it right. I’d love to get hold of a Tardis and go back and see if I got it right.

DS: The Liberty Box aside, was there anything specifically about drawing the Chartists which you found challenging?

Polyp: To be really frank, the main difficulty with Courage was just the timescale and budget. You sometimes have to choose what you’re going to draw and how many images you are going to put on the page, and the density of images versus words. If anything I think maybe the Chartism chapter lacks images of the violence that they were subjected to. I’ve got words in there about them being attacked by the cops but you know they were just constantly getting stuff thrown at them. I also wanted to leave space to explore the division between ‘moral force’ and ‘physical force’ Chartists – that felt really core to the theme of Courage. And to be honest you just draw some things because it’s going to be fast: drawing a single object takes a day, but it takes about a week to draw an entire crowd which all look like real figures. I’m not doing a cartoon style; I’m going for physical realism and there’s a lot of work that goes into that.

DS: One of the defining features of Chartism is that it was a mass movement …

Polyp: I knew that the classic photo of Kennington Common had to go in but again, partly for speed but also partly because I’m quite interested in in the mediums in which history is being recorded, I decided to show the photograph as an actual metal plate being developed. I thought that was interesting because it says something about how objects, real physical objects, record history.

DS: Finally, I want to ask you about your sketch of William Cuffay, which is one of the items which is going to be auctioned at Chartism Day. It is a wonderful drawing, not least because you’ve made Cuffay look so warm and genial. As far as I know the only contemporary image we have of Cuffay is a depiction in Reynold’s Political Instructor from c.1850. Did you draw from that?

Polyp: I was initially tempted to reproduce that image, but I just felt such a kind of love and admiration for the guy – in in a way that I didn’t for, say, Feargus O’Connor – that I wanted to do something more. You can see the warmth in his face and I thought that deserves to be a real portrait of a real person not a reproduction of the Reynold’s one, which is itself quite a cartoony image. So I spent some time searching someone with similar facial characteristics and ethnicity, and eventually found one of those standard commercial pictures you can get, of this man who resembled what we know of Cuffay, and I was able to combine my impression of that image with the Reynold’s one, to create a new sketch, which looks familiar but conveys the depth he deserves.

David Stack is hosting this year’s Chartism Day event at the University of Reading on Saturday 7 September. For more information and to register, click here.

You must be logged in to post a comment.