In the second of our two Black History Month blogs, Dr Benjamin Bland (Leverhulme Early Career Fellow in the Department of History) reflects on the importance of transatlantic exchanges and identities to the history of Black musical cultures in the twentieth century.

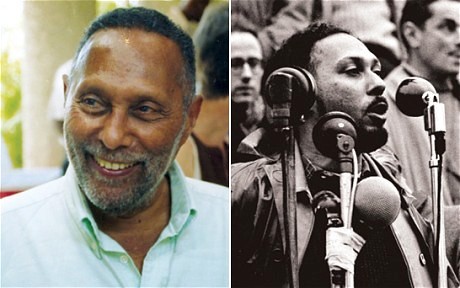

In his posthumous memoir, Familiar Stranger: A Life Between Two Islands, the massively influential Black British public intellectual Stuart Hall spends several pages musing on the role that music had played in his life, not least in shaping his own sense of self. Born in Kingston in 1932 and raised as part of the late colonial Jamaican middle class, Hall moved to Britain at the start of the 1950s to study at Oxford. His youthful experiences in Jamaica and at Oxford were, of course, foundational to Hall’s developing political and social consciousness, but – as his memoir makes clear – his music fandom also played a fundamental role. In fact, he describes his “identification with modern African American music” (and particularly jazz) as playing a “seminal” role in shaping his identity “As a young colonial of colour” who was not “yet self-consciously black”.1

Hall was far from alone in having his sense of self, and particularly his sense of Blackness, shaped by the Black musical creativity emerging from the United States in the middle years of the twentieth century. Jazz, blues, gospel, soul, and early rock ‘n’ roll were all hugely important in helping to structure Black identities well beyond the American cities in which they were first born. At a time when imperialism remained in situ throughout the Caribbean and large swathes of Africa, Black American musical creativity was central to the creation of a diasporic and transnational Blackness that linked local and global struggles for freedom and autonomy. It was only strengthened when joined to musical traditions emerging from the Caribbean and from Africa, such as Trinidadian calypso or Nigerian highlife. Ultimately, as Hall also notes, music helped in the creation of new narratives and pointed towards (in his words) the birth of a “conscious language of race” that proudly avoided “the evasions, euphemisms, double-talk, disavowals, and self-deceptions” that had previously been such a key feature of everyday Black experiences around the world.2

This Black History Month the theme is “Reclaiming Narratives”. In this spirit, a focus on music feels completely appropriate, allowing us to think through the many ways in which creative expression has been at the forefront of both challenging discrimination and celebrating Black identities. Legendary Black musicians are now widely held up all over the world as iconic figures who have played their part in bridging divides and enabling a more tolerant, multicultural society. This year’s departmental Black History Month event – “Historicising Black Musical Cultures Beyond Borders” (tomorrow, 30 October 2024, 2pm in Edith Morley 127) – explores these ideas in a number of ways, using a wide variety of examples. Everyone is very much welcome to attend and join the discussions but, in the meantime, let’s briefly take a look at a trio of tracks that speak to this transatlantic history, and which all deserve to be placed back in the limelight having been largely forgotten.

Winifred Atwell was born in Trinidad in the early 1910s, later gaining experience at the piano by playing for American air force personnel stationed near Port of Spain. After studying in the US and at the Royal Academy of Music in London, Atwell became a celebrated pianist – known for her use of boogie-woogie and ragtime stylings, although she was also accomplished as a classical player. A BBC regular, Atwell went on to become the first Black artist to have a UK number one single with 1954’s “Let’s Have Another Party”, making her one of the few Black cultural figures to achieve a major mainstream presence in early postwar Britain. Despite her stardom and frequent media presence, not to mention her acknowledged influence on a whole generation of hugely successful white male keyboard players (such as the prog rockers Keith Emerson and Rick Wakeman), Atwell is seldom remembered today.

Comprised of migrants who had moved from Jamaica to London as teenagers, The Cimarons are now often cited as the first British reggae band. This only tells part of their story. The group were influential not just on the subsequent wave of British reggae acts – such as Aswad, Black Roots, Misty in Roots, and Steel Pulse – but on Jamaican acts too. Their story therefore speaks to the mutual patterns of exchange that are such an important part of the history of transatlantic Black musical culture. As a new documentary makes clear, The Cimarons faded into obscurity in no small part because of the institutional racism they experienced within the music industry. Thankfully they are now starting to be remembered as the legendary group they are.

The very idea of “British hip-hop” is often dismissed as irrelevant compared to the music that was created by Black American pioneers of the genre. It is only in the twenty-first century that British acts such as Dizzee Rascal, Little Simz, Stormzy, and Wretch 32 have given the UK’s own hip-hop scene the widespread credibility it was often (wrongly) seen as lacking. London Posse were amongst the first British hip-hop acts of note and they demonstrate that, for as long as there have been British rappers, there have been those willing to give the genre a new spin from this side of the Atlantic. The group’s cockney accents and use of British Caribbean patwa slang allowed them to communicate their perspective on Black British life (and, as in this track, convincingly engage in bouts of typically – and problematically – sexist hip-hop bragging) at a time when many other British wannabe rap stars were still directly copying US acts. London Posse’s sound still sounds unique and distinctive to this day, no matter what one thinks of their lyrical content.

Discover more at tomorrow’s event – all welcome! Questions can be directed to the organisers: Dr Benjamin Bland (b.bland@reading.ac.uk) and Dr Dan Renshaw (d.g.renshaw@reading.ac.uk).

You must be logged in to post a comment.