James Smith, finalist in BA History, traces the evolution of Father Christmas in Britain across the nineteenth century.

Father Christmas driving a car! Even in the twenty first century, the idea of him piloting anything other than a sleigh seems weird. What is even weirder is that the above cartoon, published in Punch, was published in 1896. The transition from the last few years of the nineteenth to the first few years of the twentieth century has been identified as turbulent. New ideas were gaining friction and old ones were fading faster than ever before, all under the guise of developing modernity. The iconography of Father Christmas was involved in this transition and was used to articulate new ideas of Christmas or society more generally. So, pull up a chair by the fire and settle down for a read on how Saint Nick entered the twentieth century.

The Origins of The Man Himself and the Early Twentieth Century Christmas

Father Christmas first appeared in the UK in a fifteenth century Christmas carol by Robert Smart, where ‘Sir Christëmas’ heralds the birth of Jesus. This idea was then incorporated in the popular midwinter festival of misrule, a festival that included drinking a lot of alcohol and mocking authority figures. Leaders of the festivities pretended to be Captain Christmas or Prince Christmas whilst getting drunk. This image was crystallised by Ben Johnson’s Christmas, His Masque where Father Christmas was depicted as a bearded man in long robes. This man stayed the image of Christmas until the Victorians came along. The Victorian era saw a change in societal ideas and notions. Their obsession with familial relationships transformed the festivities and placed gift giving and children at its centre.

However, Father Christmas developed in parallel with Santa Claus. Claus began with Saint Nicholas who gained popularity in medieval Europe through his religious day (6th December) where gifts were given to the good. His legend expanded to include demons, such as Krampus in Germany, who punished the naughty and in the Netherlands the emergence of Sinterklaas as the bishop dressed gift giver. Sinterklaas went with the Dutch settlers to New Amsterdam (New York) in America and his continual celebration, alongside linguistic and literary change, resulted in Santa Claus, the sleigh riding gift giver. As the nineteenth century drew on, Father Christmas began to take aspects of Santa Claus to adapt to the Victorian’s changes and eventually the two became the same man in the popular imagination.

This iconic character entered the twentieth century. However, Christmas was also changing. Historian Neil Armstrong noted how with the rise of department stores such as Gamage’s, the first commercial chain to sell toys all year round, that Christmas was changing from traditional festivities to a consumer event. Annie Gray explains how Christmas dinner went from elaborate platters of pheasant and other game to a more modern and uniform array of turkey and all the trimmings. Society was changing and Father Christmas was caught in this festive variation of the modernising process.

Santa Without a Beard!

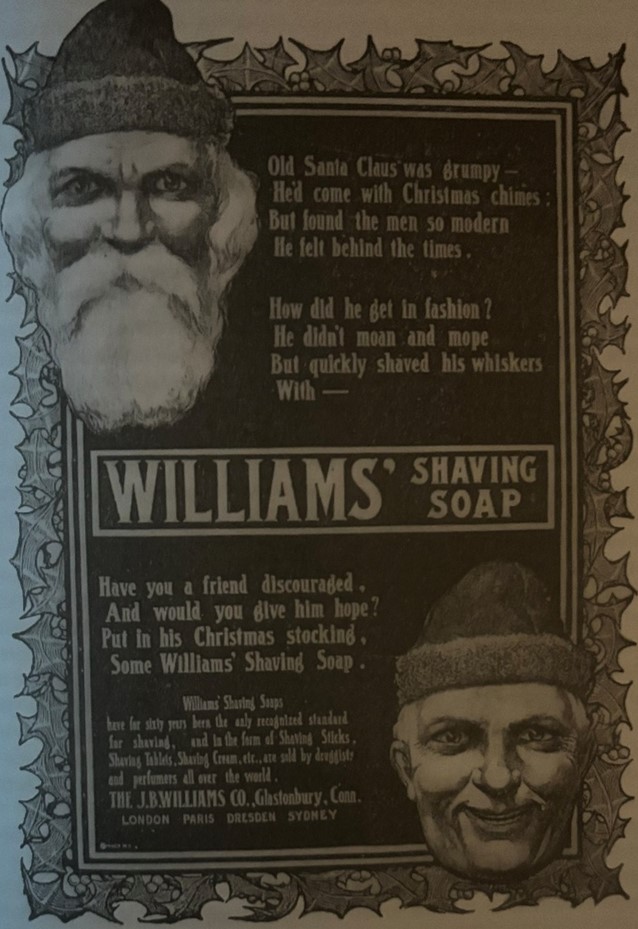

Some groups looked to use Father Christmas to articulate new ideas. This advert in the Illustrated London News, for William’ shaving soap, is one of the more extreme attempts, where Santa removes his beard:

Santa without a beard! That is like Christmas without a tree! Yet the shock, plus William’s message about the modern man being clean shaven, shows how the jolly man was used by the emerging consumer marketing. These attempts, while they were satirical, placed the icon alongside changing values and ideas (shaving was ganning popularity with men after Gillet invented the disposale razor in 1895) and shows how Father Christmas was interacting with the modern age. Obviously, the attempts to shave him failed. Whilst he did not change much from his earlier depictions (Beard, man, old fashioned cloths, and a ridiculous hat) his sesonally constant, and unchanging, presence in society created a subtle way to articulate innovative ideas. Armstrong argues that, although he rarely changed, his pressense acted to show new ideas about festive Fatherhood and Fatherhood more broadly.

New Queen, New Santa

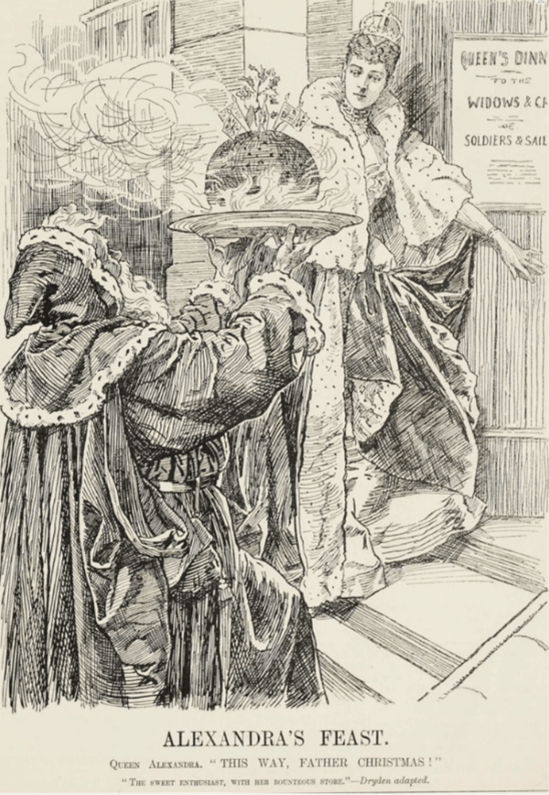

Williams were not alone in using Father Christmas to send a message. Punch was famous for doing this. One such case, where they used Saint Nick to send a message, was their political take on Queen Consort Alendrendra of Denmark’s philathropy.

Whilst this captures how Alexandra, the new Queen Consort after the long reigning and socially molding Queen Victoria, was changing the roles of the monarchy, something else can be seen in this image. Father Christhmas, who is carrying the Christmas pudding, looks different from his earlier represntations.

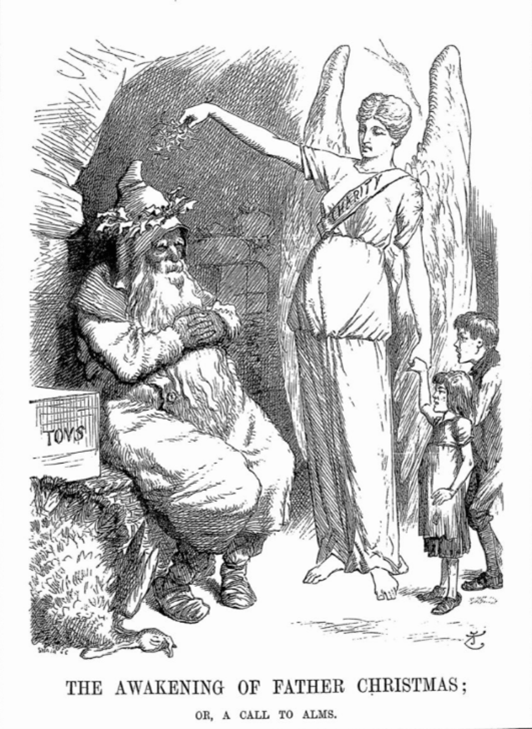

The two cartoons, only eleven years apart, depict Father Christmas in contrasting outfits and with a slightly different length of facial hair. There are multiple reasons why this could be. Different artists (although other pre-nineteenth century cartoons in Punch depict him in a comparable manner to the second image) or changing depictions of Father Christmas in the broader imagination. This change is not confined to Punch either and thus shows that his appearance was changing as the nineteenth century ended and the twentieth century began. The best explanation is given by Tom Moriarty who states that the gradual adaptation of Father Christmas with aspects of the Santa Claus myth resulted in the two becoming the same person. This process continued, and was completed, in the early twentieth century, where depictions of the two became more alike.

That is how Father Christmas entered the modern age. He was already undergoing a transformation to include elements of the Santa Claus legend. This process was continuing as the century ended. Furthermore, he was, as an idea, used to articulate new ideas and to help progress modernity in the festive season. With this read over, I wish you the very best Christmas.

Further Reading:

Armstrong, N., ‘Father(ing) Christmas: Fatherhood, Gender and Modernity in Victorian and Edwardian England’ in Broughton, T. L and Rogers, H. (eds.), Gender and Fatherhood in the Nineteenth Century (Basingstoke, 2007), 96-110.

Armstrong, N., Christmas in Nineteenth Century England (Manchester, 2010).

Clegg, S., The Dead of Winter: The Demons, Witches and Ghosts of Christmas (London, 2024).

Gray, A., At Christmas we Feast: Festive Foods Through the Ages (London, 2022).

Moriarty, T., ‘The History of Father Christmas’

Simpson, J. And Roud, S., A Dictionary of English Folklore, (Oxford, 2000).

You must be logged in to post a comment.