Dr Liz Barnes discusses the difficulty of uncovering ordinary queer lives in the past. Please note that this post contains references to sexual violence and language that readers might find offensive.

Criminality is ever-present for historians seeking to uncover queer lives in the American past. Prior to the reforms of the twentieth century in the United States, same-sex desire and gender non-conformity were most visible when they were policed. In the absence of marriage certificates, we have sodomy charges; in place of drag portraiture, cross-dressing convictions. Though there is a flourishing field studying queer[1] life in the United States, that field’s reliance on criminal records has always sat uneasily. How can we wade through layers of dismissal, humiliation, and punishment to celebrate the diversity that has always characterised the human experience?

We only know that Frances Thompson was queer because the Memphis police criminalised her for it. Born into slavery between 1824 and 1840 in one of the eastern states, Thompson was carried to Tennessee by her enslaver prior to the Civil War. The federal government’s Emancipation Proclamation of 1863 granted Thompson her freedom, though she chose to remain in Memphis with the Black community she had settled into rather than return east. Thompson fell foul of city authorities on several occasions, facing frequent arrests for ‘lewdness’ and ‘keeping a disorderly house’, nineteenth-century crimes associated with sex work. Like many of her impoverished peers, Thompson appears to have engaged in sex work to supplement the income she earned doing other traditionally feminine labour: washing, ironing, and sewing. Her friend and housemate, Lucy Smith, worked alongside her both as a laundress and a sex worker. The pair were often detained by the police together.

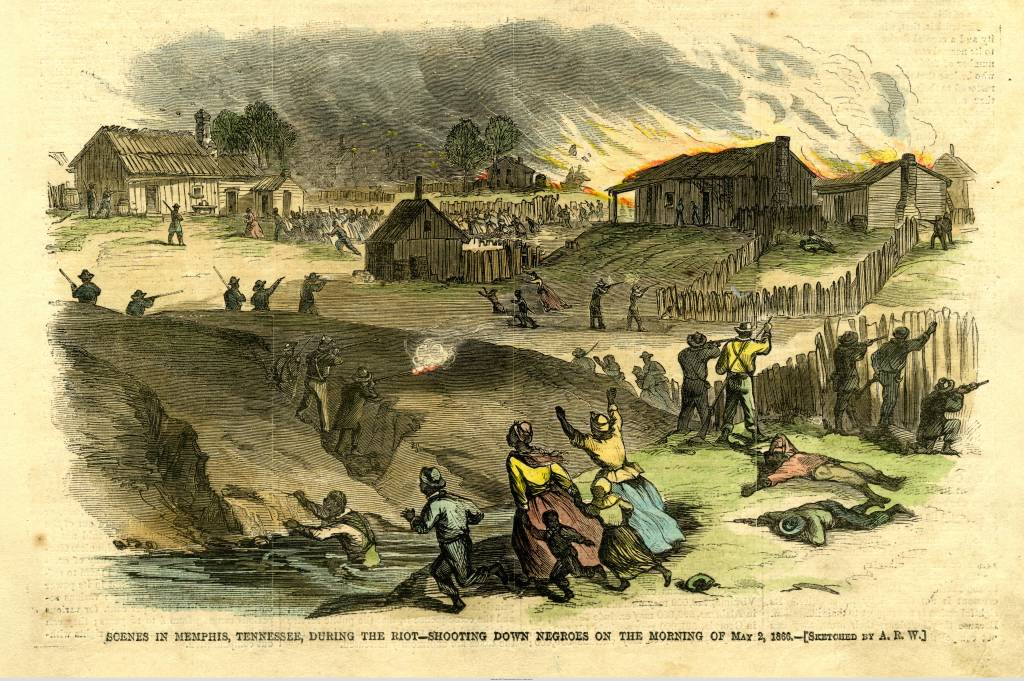

Thompson’s own voice first entered the archive in 1866. Memphis was a hotbed of unrest after the Civil War, when established white communities had to grapple with the after-effects of the conflict, including emancipation, Black migration to urban centres, and ongoing power struggles as the nation tried to rebuild. Tensions in Memphis were particularly high between the police – a locally controlled, entirely white force – and the soldiers stationed in the fort, who were a Black regiment of primarily formerly enslaved men. These hostilities erupted into violence in early May, when the police attacked a group of Black troops before rampaging across the city, burning Black homes, businesses, schools, and churches, and assaulting Black individuals. In the ensuing investigation, five Black women testified that members of the mob had raped them.

Frances Thompson and Lucy Smith were two of those five women. A group of men including police officers in uniform broke into their home and raped them. Though doubts have since been raised about the veracity of Thompson and Smith’s testimonies, their words had a major impact on the political landscape in the post-emancipation US [2]. The riot helped the federal government to argue that white supremacy was rampant in the South, gaining support to enact more radical policies that addressed inequalities that lingered after the death of slavery. The political significance of the freedwomen’s testimonies is precisely why city police and the local Democratic Party targeted Thompson a decade later, in 1876, on the eve of the presidential election [3].

In July 1876, police officers once again arrested Frances Thompson under suspicion of engaging in sex work. Their other motive was apparent, however, when the arresting officers transported Thompson to a station house where they ordered three doctors to examine her nude body. These doctors determined that Thompson was ‘a man and not a woman in any respect.’ Thompson was charged with cross-dressing, convicted, and ordered to carry out her sentence working on the city’s chain gang – a punishment reserved exclusively for men. Stripped of her own clothing and forced to wear male garments, the police made a spectacle of Thompson. Spectators followed the gang hurling insults at the freedwoman and scuffles frequently broke out between Thompson and those who gathered to leer at her. Already disabled at some point during slavery, Thompson was of little value to the labour gang – she was there to be seen and humiliated, not to work. Through ‘unmasking’ Thompson, Democratic authorities hoped to undermine Black claims of violent white supremacy in the South and destroy the reputation of the local Republican Party; their eventual aim was to esnsure the election of a Democratic president. In their desire to make a spectacle of Thompson, however, Memphis authorities gave her another opportunity to speak about her own life. Thompson conducted interviews from her cell, with local newspapers keen to prifit from the scandal of ‘Crutchy’, ‘infamous […] keeper of one of the vilest dens’ in Memphis. From these interviews we can piece together a story of Thompson’s life, told on her own terms and framed through her own experiences.

Though Thompson did not refute the doctors’ allegations that she had a male body, she did argue that she had always been ‘of double sex’ and that she had lived her life as woman, both in slavery and freedom. Thompson appears to have done so openly – she was known in Memphis as ‘the hermaphrodite’ of Gayoso Street, a clear reference to her ambiguous gender identity (though this is not evidence that she was what we would now call an intersex individual – the term ‘hermaphrodite’ did not exclusively refer to biological sex in the nineteenth century, but also included an understanding of the social nature of gender identity). Thompson was firmly embedded in the community, working successfully as a laundress alongside infrequent sex work and seasonal work as a fortune teller. She had a close relationship with Lucy Smith, with whom she shared a home and a bed. The press implied that Smith and Thompson were sexually involved, referring to Smith as Thompson’s ‘paramour’, though Thomspon did not confirm this herself, and platonic bed-sharing was common in the nineteenth century. Though the subject of a major political scandal, Thompson expressed no interest in party politics.

Despite Thompson’s attempts to wrestle back control of her own narrative and identity, ultimately the conviction was her undoing. Though she responded to the press and aggressive spectators with spirited defiance, Thomspon was a disabled woman unsuited to hard physical labour and the stress of her confinement in the city jail. Thompson contracted pneumonia as a result of her ill-treatment, suffering in a home outside the city before she eventually died at the city hospital on November 1, 1876. She was, according to city records, 52 at the time. By her own account, she was just 36 years old.

There is a final significant detail about Thompson’s life that we learn from her criminalisation and death. Although the conservative press worked hard to establish that Thompson was ‘hated and feared’ by the Black community, the freedwoman evidently maintained significant relationships until the end of her life. It was a group of local freedpeople who discovered Thompson ailing in her hut and brought her to medical professionals in the city. These individuals did not see her as a dangerous deviant, as the city officials had presented her, but rather a person worthy of respect, care, and love. Through the veil of a dehumanising criminal case and newspaper scandal intended to manufacture a monster, Frances Thompson’s very ordinary life shines.

[1] Though once used as a derogatory term, ‘queer’ has been embraced by the LGBTQ+ community as a useful, catch-all term to refer to a number of identities that sit beyond heterosexuality and forms of gender expression and identity deemed normative.

[2] See Stephen V. Ash, A Massacre in Memphis: The Race Riot that Shook the Nation One Year After the Civil War (New York, 2013), n. 57, pp. 236-8.

[3] At this time, the Democratic Party opposed the emancipation of enslaved people and supported maintaining white supremacy through legalised inequality.

Further Reading

Hannah Rosen, Terror in the Heart of Freedom: Citizenship, Sexual Violence, and the Meaning of Race in the Postemancipation South (Chapel Hill, NC, 2009)

Ardel Haefele-Thomas, ‘“Under False Colours”: Nineteenth-Century Masquerading Laws and Black Disabled Transgender Embodiment in Post-Civil War Memphis’ in Royce Mahawatte and Jacki Willson (eds.), Dangerous Bodies: New Global Perspectives on Fashion and Transgression (New York, 2023).

You must be logged in to post a comment.