Our PhD student, Fiona Lane, shares what she has learned about the woman who rasied her grandfather Jack.

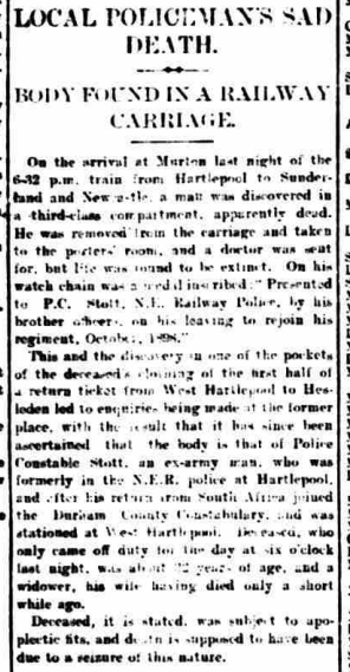

Sarah Blenkinsopp’s (1857-1937) story starts, for me, with the tragic death of my grandfather’s parents. It is very unlikely that Sarah would have been remembered in my family otherwise, or that the family would even exist. My grandfather, Jack Stott, was born on 6th May 1903, in Hartlepool. Ten months later, his mother died in Darlington, aged 29, of gestational diabetes. Just two months later, his father, a police constable who had served in the South African War (or Boer War), was found dead on a train travelling from Hartlepool, caused by ‘apoplexy’. An infant so orphaned, one would have assumed, would have been taken to the local workhouse.

There was no welfare state and no formal adoption process in 1904, but at some point (he appears not to have been with his mother when she died), Jack went to live with his great aunt, Sarah, at the Gardener’s Cottage, Brettanby Manor, Barton, Yorkshire – he was listed as living there in the 1911 Census. Here, aged 7, he was living with Sarah, her husband Charles (1862-1936), gardener and domestic servant, and his daughter, Hilda, a draper’s cashier, and another nephew, who was a bricklayer and lodger. But Hilda was not Sarah’s daughter, and nor were her older sisters, Olive and Emily. Delving further into the records, Charles’ first wife Emily had died in 1893, a month after giving birth to their fourth child, Charles Edward. Sadly, the baby also died just six months later.

The widowed father married Sarah in 1894. It is unclear whether Sarah moved into Gardener’s Cottage to look after Charles’ young daughters, at the time between 3 and 7 years old, or if she married him before she moved in. It would not be unusual for a widowed father to seek professional help to care for his children. Charles and Sarah had much in common that might have brought them together: Sarah was also widowed, having lost her first husband Caleb Alderson, a quarry owner, in 1891. Her remarriage was not just for companionship, though – like many working-class women at the time, Sarah understood that marriage was the main way to secure a more economically stable life. She knew how difficult life was for a widow, having been raised herself by only one parent. Born Sarah Stott, she was the youngest of at least five children to John, a shoemaker, and Ann, who lived in Blackwell, Darlington. Ann was widowed by the time of Sarah’s 14th birthday – in the 1871 Census, she was described as a ‘shoemaker widow’, who also had two male boarders, both shoemakers. After her husband’s death, Ann had to keep the business going for the sake of her children.

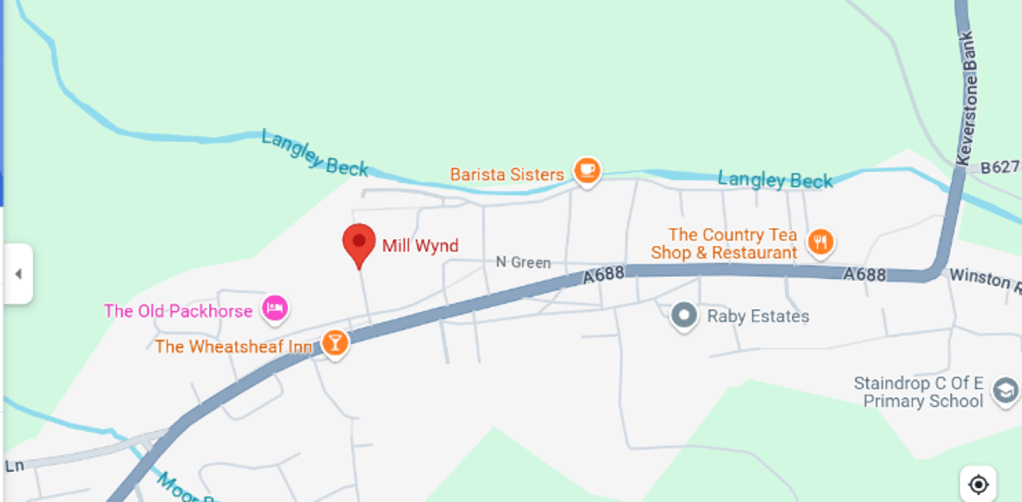

Despite the tragic ends of their first marriages, Sarah and Charles shared a long life together. As Charles grew older and probably unable to cope with the extensive grounds of the Brettanby Manor, he and Sarah moved to Mill Wynd in Staindrop where Charles continued to work as a gardener. Jack, firmly a part of their family, maintained a close connection all his life. It was in their Staindrop house that Jack’s son, my father, was born in 1938. My father never knew Sarah and Charles: Charles had died in 1936, followed by Sarah a year later. My grandfather, perhaps having learned frugal habits from Sarah, had by that time saved enough money to buy a house across the road.

Sarah had no children of her own, but she brought up four children. It is clear from my father’s recollections that Jack never thought of Sarah as anything other than his mother. I remember a blurred photograph of my grandfather as a young man with hair (he was always bald to me) shown to me as a child. In it he had his arms around a tiny woman dressed in Victorian clothes and they were both laughing, the camera catching a moment of tenderness. This was Sarah.

It seems as if very little of this story is about Sarah, but this is the story of many women in the past. She took the only role that nineteenth century women had – to be a mother and carer, even if she had no children of her own. Just like all women of her class, she remained in the shadows, barely acknowledged in the records, with no paid occupation, no property and invisible to much of society.

Yet, like all women like her, she had a huge impact on the lives of those around her and to society in general. Particularly in an era before the Welfare State, people could not survive without the unpaid labour of women. It appears she also did a fine job. All her ‘children’ led fulfilled lives. Hilda married, and Olive became a general servant and then worked as a cook in large houses. She never married, but she made it into the local Richmond press in the 1940s due to her work as a stage manager to local amateur dramatic performances. Emily also never married but, despite coming from such a modest background, worked as a trained nurse and by 1939 was a hospital home helping sister in Kent.

My grandfather followed Charles into gardening but soon realised there was more money in labouring on the LNER Railway. He never lost interest in his allotment, though, which he kept until shortly before his death aged 90.

Sarah encapsulates the history of women, and Women’s History Month is a celebration not just of women who had unusual or important roles in public life, but also those who were the backbone of society.

You must be logged in to post a comment.