PhD student Fiona Lane shares some of her own research in the aftermath of the VE80 celebrations, focusing on very different types of street parties: those hosted by rent strikers in the 1930s.

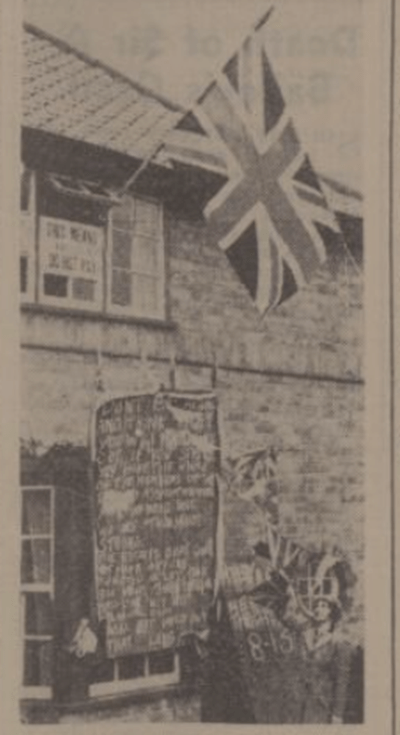

‘It will be like Coronation Day again!’, exclaimed an organiser in Birmingham to her neighbours as they hung bunting from their houses and chalked slogans on the road. On municipal housing estates across England there was a similar flurry of activity: women dressed in sandwich boards and paper hats and carried banners and union flags.[3] In Sunderland and Birmingham, there were charabanc trips of flag-waving women and children to other estates and the council offices.[4] In Amersham, prizes of free cinema seats were given to the best decorated houses.[5] Children dressed up in fancy dress, swimsuits and union flags and some residents even festooned their houses with patriotic pennants like Mrs Wallace of Caldwell Road, Birmingham.

The reader would be forgiven for believing that these descriptions came from accounts of VE Day in May 1945, but they belonged to a period six years earlier, when mostly female municipal tenants withheld their rent across England in response to rent rebate schemes and rent rises to make up the financial shortfall caused by a savage cut to the central government slum clearance subsidy in 1938. This was to free industry resources for rearmament as war approached, but for municipal tenants, it meant on average subsidised rents rising by 2s 9d.[7] Arthur Greenwood, deputy leader of the Labour Party, told parliament: ‘[t]he local authorities…fear – quite rightly, it seems to me – that the rents will rise, in which case, if my prophecy comes true, the poor will pay a heavy price for this….rearmament programme’.[8] It is unknown exactly how many strikes succeeded or failed because, as Britain hurtled towards war, some outcomes were never reported in the press.

Rent strikes reported in the local press suggest an atmosphere of carnival and community entertainment at odds with the tenants’ grievances and demands, which had gone unheard for years. Women realised that strength lay in communal activities and engaged in lie-downs, throwing soot, broken glass and flour at the bailiffs who were sent in to recover the money they owed by distrain, or even to evict them. They erected barricades and managed to block off entire areas of the new cul-de-sac-ed estates.

The press was keener to report the more humorous and enjoyable elements of their protest, however, perhaps to encourage its readers to believe the women were harmless and merely hysterical, feckless or led astray by the Communist Party (CPGB), which was in evidence on some estates. Rough music accompanied rent collectors, with women and children shouting, ringing handbells which sounded ‘suspiciously like an ARP bell’, playing on kitchen utensils and leafleting others until they gave up trying to collect money.[9] They sang songs, putting new words to popular tunes such as Daisy, Daisy, Blaze Away and I’m Gonna Lock My Heart.

Strikers also put on plays: the Left Book Club Theatre Guild (LBCTG) visited striking Sunderland estates to provide street theatre performances of short plays about the concurrent rent strikes in London. It performed an adapted version of Simon Blumenfeld’s Enough of All This! A Rent Strike Play, where it was welcomed enthusiastically by ‘practically everyone on the estates’.[10] While the LBCTG performed for them, the women were not passive spectators. A cast member reported that they blocked off the street to traffic, made a platform from their tables for the performers, provided many of the props and even provided a real baby for the actors to hold.[11]

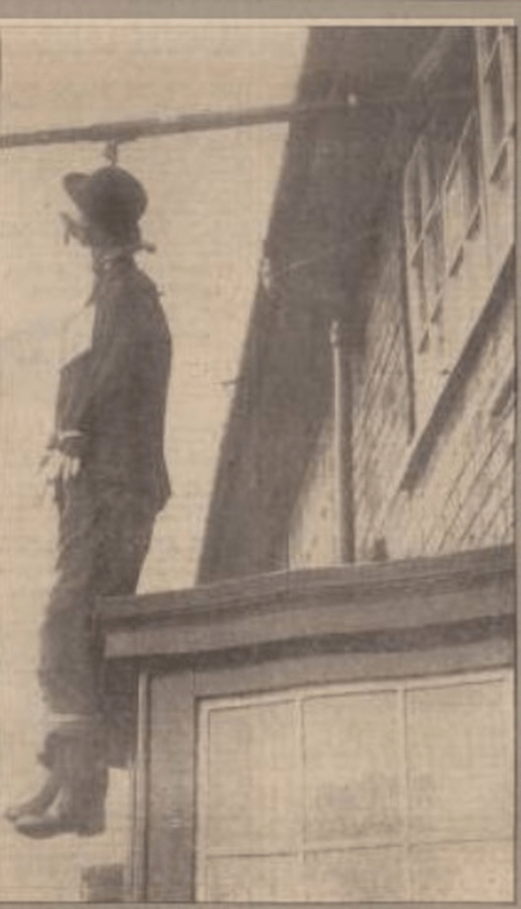

In Birmingham, they made their own plays: several enactments of catching a ‘skulking bailiff’ were performed at meetings, and ‘street performances of plays written and acted by rent strikers’ were a regular feature, the most popular one involving audience participation chasing him over a garden wall. The Weoley Castle branch advertised their social events, including ‘mock trials’ in the July 1939 edition of Community News, a local newsletter.[12] A ‘jury of dancers’ ‘tried’ an effigy of a bailiff and found him guilty: it was then hanged, and the ‘funeral’ was held the following day when the 50,000th house was opened by the city’s mayor the following day to a crowd of 3,000 tenants. ‘Women predominated’ and they used symbolic touches: ‘(t)he brass handles of the coffin (were) the door knockers of four strikers.’ There was a mock clergyman and ‘”(m)ourners,” some of them dressed in deep black made up the make-believe cortege and pretended to be overwhelmed with grief.’ The coffin, ‘draped in a yellow cloth’, was then buried in a nearby drain ditch as women threw soil and lay wreaths on the coffin.[13]

But many of the protests took on a darker tone. Borrowing the CPGB’s tactic of sending a coffin the 10 Downing Street, coffins and other symbolism were used in a less humorous way.[15] In Amersham, they drew pictures of coffins, bearing the initials of ARDC (Amersham Rural District Council), with the slogan, ‘It’s their funeral,’ underneath.[16] The Sunderland strikers also carried a coffin on demonstrations and in Willenhall, they recognised they could be menacing when acting in unison and their allegiance to each other as women was evident: ‘they ceremoniously hanged a dummy bailiff from the lamp-post’ because bailiffs had entered an expectant mother’s house through a window.[17] In Kenton, just like in Willenhall, effigies of bailiffs hung outside.[18] Even the performances were intended to be disrespectful and intimidate those in authority and were an extension of the women’s protective behaviour. They may not have used violence, but they used traditional derisory techniques. Even small touches such as the use of door knockers or ARP bells were symbolic of scorn.

The strikers may have protested and derided those in authority, but their use of Union Jacks does not seem to be ironic and suggests their desire to be seen as patriotic. Mrs Wallace’s flags, perhaps emphasising her patriotism as war became a distinct possibility, also demonstrate Ross McKibbin’s argument that nationality was ‘simply a casual assumption of everyday life’.[20]

There is also evidence that on municipal estates, in contrast to the description by the later Communist MP, Phil Piratin, of the East End where he claimed enthusiasm for the 1937 Coronation was exaggerated so ‘the capitalist class and their press lackeys (could) delude themselves that this response was an indication of faith in capitalism and subservience to the State’, there was an admiration for the royal family.[21] The monarchy embodied ‘certain fundamental moral standards’, it was emotionally pleasing and politically uncontentious and represented ‘fairness’ in society.[22] To admire the monarchy meant a belief in a well-ordered nation.

This was not a revolution questioning gender roles or attempting to dismantle existing society. The women protested as consumers and reproducers because suburban life meant there were few opportunities for paid employment. They were treated as wives and mothers who had to juggle, manipulate and think of new initiatives to budget money over the amount of which they had no control. They did not define themselves as protestors against consumption, but they complained about the position it placed them, as mothers of hungry children, as ‘saving’ money by not paying the rent and not having to go to the pawn shop: their concerns were high rents and low wages. CPGB involvement may have hidden their motives or made contemporaries believe they were the same, but their actions were borne of desperation and an attempt to ameliorate their plight. If they hoped to be heard by stressing their patriotism and ‘respectability’, they were poorly rewarded. Unlike private tenants, who had a rent freeze on 1st September 1939, municipal rents were not controlled even though their dwellers were ‘in no less need of protection’.[23]

Fiona Lane is a PhD researcher at the University of Reading.

[1] ‘Bells, Flags – and Bathing Costumes – in Big Procession’, Evening Despatch, 6/6/39.

[2] Evening Despatch, 26/5/39. https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/

[3] ‘Women’s Rent Strike’, Shepton Mallet Advertiser, 12/5/39. ‘Women Strikers Hold Up Council’, Daily Herald, 17/5/39. ‘Bells, Flags – and Bathing Costumes – in Big Procession’, Evening Despatch, 6/6/39.

[4] Nice Trip For Ninepence – Round The Council Houses’, Evening Despatch, 24/5/39. ‘Rent Strikers Go TO Newcastle’, Sunderland Daily Echo and Shipping Gazette, 3/7/39.

[5] ‘No rents to Council’, Daily Herald, 20/5/39.

[6] Evening Despatch, 1/5/39. https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/

[7] Marion Bowley, Housing and the State, 1919-1944 (London, 1945), 167. Stephen Merrett, State Housing in Britain (London, 1979), 60.

[8] Housing (Financial Provisions) debate. (Hansard, 17/2/38)

[9] ‘No Rent For The Collector Today’, Birmingham Daily Gazette, 1/5/39. ‘LCC Tenants’ Strike Deadlock’, Daily Herald, 2/5/39. ‘Women on Rent Strike Hiss Council’, Daily Mirror, 17/5/39. ‘”Strike” Over 6d Rent Rise’, Sunderland Daily Echo, 5/6/39. ‘Rent Battle’, Birmingham Mail, 19/6/39. ‘South L’pool Tenants Join Rent Strike’, Liverpool Evening Express, 21/6/39. ‘Longview Rent Day: Collectors There’, Liverpool Echo, 21/8/39.

[10] Watson, Sunderland Rent Strike, 114. ‘Left Book Club Theatre Guild: The Guild must keep step with events’ by Frank Jones, Left News (Left Book Club Journal’, No 40, August, 1939), with grateful thanks to Don Watson, shared from his personal collection.

[11] Watson, Sunderland Rent Strike, 111, information from Mr William Hunt Vincent of Sunderland. Don Watson, Theatre with a Purpose: Amateur Drama in Britain 1919-49 (London, 2024), 127, with grateful thanks to the author.

[12]Sarah Glynn, ‘For Better Housing and Against Fascism: the East End Strikes of the Late 1930s’, History Workshop, 28th September, 2021 (accessed 4/7/23) ‘Mass Trial For “Skulking Bailiff”’, Daily Worker, 19/6/39. Community News, July 1939. Birmingham Archives, L21.4/4;413230.

[13] ‘Kingstanding Awaits Bailiffs – With Flour and Soot’, Evening Despatch, 12/6/39. ‘Tenants “Bury” A Coffin As Mayor Speaks’, Daily Worker, 21/6/39. ‘Rent Strikers Stage A Mock Funeral’, Birmingham Daily Post, 21/6/39. ‘Bailiffs Driven Back By Tenants On Four Estates’, Daily Worker, 20/6/39. ‘Rent Strikers Stage Mock Funeral’, Birmingham Mail, 20/6/39.

[14]Birmingham Mail, 20/6/39. https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/

[15] ‘Camping In Behind Kenton Barricades’, Daily Worker, 24/7/39.

[16] ‘The Song of the Rent Increase Resisters’, The Buckinghamshire Examiner, 19/5/39.

[17] ‘Increased Rents Cause Strike’, Daily Worker, 14/7/39.

[18] ‘Camping In Behind Kenton Barricades’, Daily Worker, 24/7/39.

[19]Evening Despatch, 12/6/39. https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/

[20] Ross McKibbin, ‘Why was there no Marxism in Great Britain?’, Ross McKibbin, Ideologies of Class, (Oxford, 1990),24.

[21] Piratin, Our Flag, 30.

[22] McKibbin, No Marxism,18-19.

[23] ‘Tenants Gain by Rent Act, Need New Reforms’, Daily Worker, 7/9/39.

You must be logged in to post a comment.