MA student Ruth Weber reflects on one of the most moving collections held in the archives at the University of Reading: tile fragments gathered from the ruins of the atomic bomb attack on Hiroshima, 6 August 1945.

Tiles. What comes to mind when you think of tiles? Roofs, rain…certainly not radioactivity. Unless, of course, you are an archaeology student, seemingly mundane objects do not stir a great deal of excitement. However, in the Special Collections at the University of Reading, there is a collection of tile fragments that bear witness to human tragedy, each

fragment conveying the memories of lives lost.

This summer marks the 80th anniversary of a pivotal, haunting moment in history: the first atomic bomb detonated in warfare devastated the city of Hiroshima on the 6th of August 1945. As the years pass, it becomes vitally important we preserve the memory of the scores of lives slain in this violent act of war.

Mushroom clouds, death, and devastation – these are all at the forefront of our minds when we think of atomic weapons, but we are lucky enough to live in a country where these are not an imminent threat. We must not let it become a distant fear. We must not remain out of touch. The Hiroshima tiles preserved at the Museum of English Rural Life

serve as a surviving relic, transporting contemporary viewers back to the tragedy.

5930

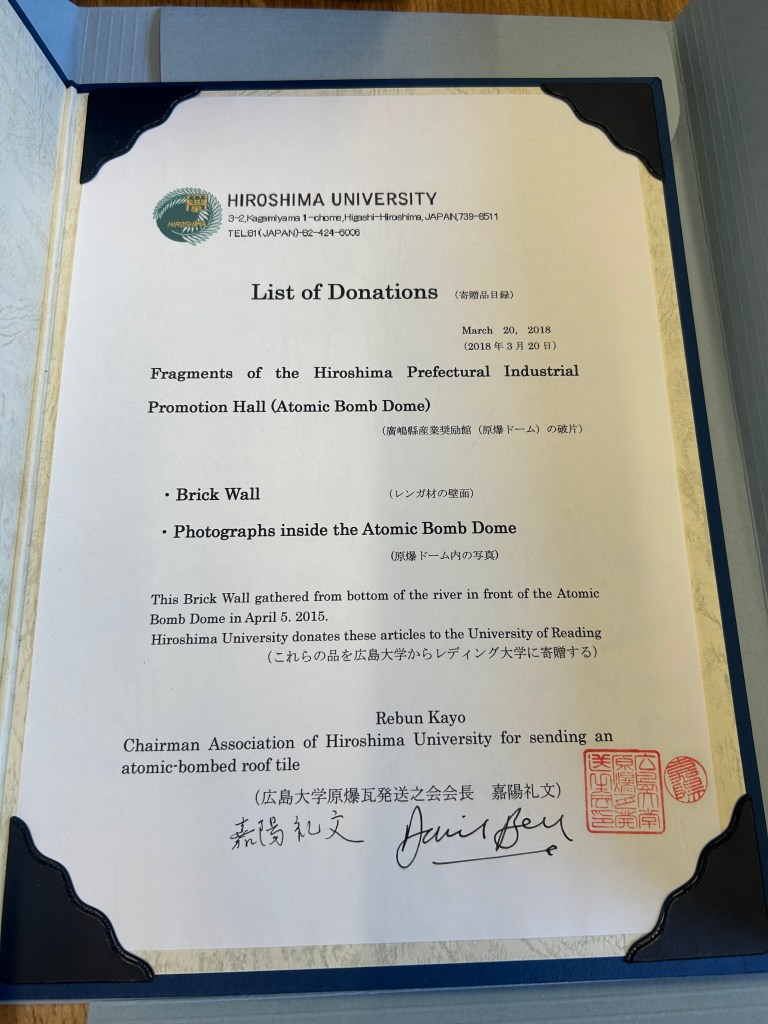

The tiles have travelled all the way from Hiroshima to the University of Reading and represent a gift from one university to another. There were two separate giftings of the tiles, the first in 2011 and the second in 2018. The first set of tiles were excavated from a riverbed near ground zero of the explosion. The second followed the 70th anniversary of the Hiroshima bombing attack where Dr Jacqui Turner and Dr Mara Oliva, of the Department of History at the University of Reading, organised a public event showcasing the first gifting of the tiles. This fulfilled the intentions of why the tiles had been sent: to spread the message of peace and advocate for the abolishment of nuclear weapons. The showcasing of the tiles deeply moved Reuben Kayo, the Chairman of the Association of Hiroshima University for Sending an Atomic-bombed Roof Tile. He subsequently organised a second shipment of tile fragments to be sent over. These were special, having previously made up the Hiroshima Genbaku Peace Dome, formerly the Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall.

Blackened, jagged, and broken, yet still depicting some of their original and beautiful design, these tiles become a relic of a great tragedy. For the hibakusha – literally, ‘bomb-affected people’ – the objects that survived the atomic bombing, like these tiles, hold a deeply emotional connection to the souls who passed away. In the paperwork accompanying the donation, Reuben Kayo of the University of Hiroshima wrote: ‘Atomic-bombed roof tiles have absorbed blood and bodily fluids of tens of thousands of people who were inhumanely burned dead.’

Allow a minute to let that sink in.

The significance of the tiles being taken from a riverbed is brought into harsh realisation. Kayo paints a tragic picture of the last hour of the victims’ lives: ‘They were burned by the 5000°C heat rays, leaving their skin scorched black, and the functions of their organs was destroyed by the radiation. They were desperately seeking water while repeatedly vomiting, bleeding all over their bodies and throwing up blood. When they finally reached the riverbed in their hour of death, at the end of their strength they collapsed, only to be washed away in the river.’ Extracted from this very same river, these tile fragments take on a revered status and must be protected.

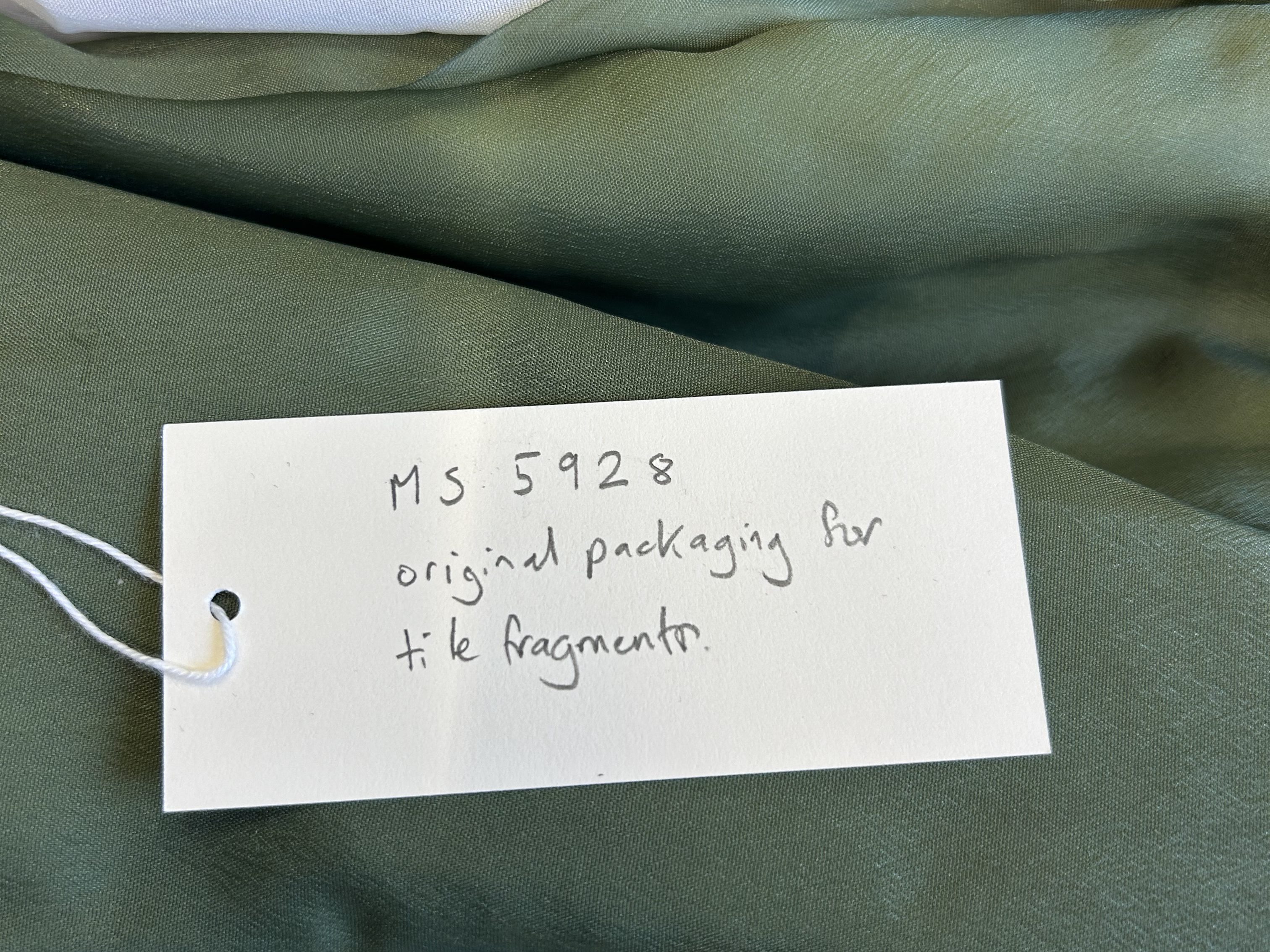

From this correspondence, we are able to understand how the tiles become akin to a corpse, and instead of remaining a mundane object, they take on a life form of their own, serving as a reminder of the souls who subered horrific deaths. They were sent with the intention of silently conveying to those far removed from the tragedy the sheer subering that those at Hiroshima endured. Originally, the tiles were sent wrapped in silk burial cloth, which is now preserved alongside them. It is evident that they must be treated with the utmost respect for the embodiment and incarnation of the loss they represent.

This is why the University of Reading values these tile fragments so deeply. They are used in lessons so that students are not only able to learn about the history of the Hiroshima atomic bombing but further connect with the past on an emotional level. These tiles provide a pivotal contact

with the past, and viewers are able to form a tangible connection to the sorrow and loss that the hibakusha felt after the bombing.

By maintaining the memory of the atomic bombing, the hibakusha’s mission of peace is greatly facilitated. They were donated to the University of Reading with the University of Hiroshima’s ‘wholehearted wish for the realisation of a world free of war and nuclear weapons.’ Amongst the correspondence preserved with the tiles at the Museum of English Rural Life are words from the former Mayor of Hiroshima,

Kazumi Matsui, in acknowledgement of the 70th anniversary of the Hiroshima bombing. He captures the goal of the hibakusha, and the intention behind the tile giftings, perfectly: ‘To make sure the tragedies of Hiroshima and Nagasaki never happen a third time, we hope that as many people as possible will communicate, think and act together with the

hibakusha for a peaceful world without nuclear weapons and without war.’

We must ask ourselves how we can live in a world of peace when nuclear weapons still exist; even being used as deterrence, the possibility of global annihilation still hangs in the balance.

This summer, then, around the excitements and joys of British summertime and holiday living, will you mark the 6th of August in your calendar and remember the lives of those slain by the violence of mankind?

You must be logged in to post a comment.