As part of the University’s Centenary Celebrations, a team led by David Stack in History has been researching the experiences of students and staff from working-class backgrounds at the University of Reading. Beginning with the widening participation roots of the University in the 1890s Oxford Extension movement and coming right up to date with policy recommendations for a more socially inclusive campus, the team have aimed to highlight working-class presence, celebrate success, and acknowledge ongoing challenges. Over the next few weeks, we are going to publish a series of linked blogs exploring some of the themes the team have been working on. We begin with David Stack reflecting on his experience of ‘Going to University’.

I should never have gone to university.

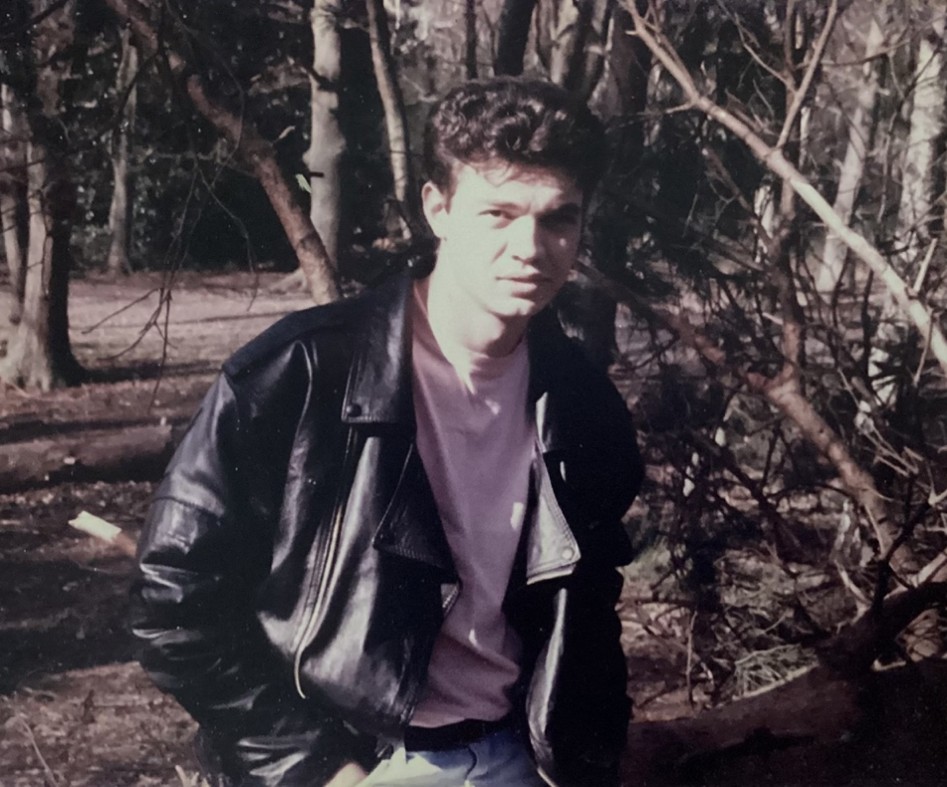

By which I mean statistically it was a most unlikely thing to happen. I finished my A-levels in 1987, before the 1990s massification of higher education, and I did not come from an educational background. Both my parents left school at 15. My dad – who had attended ten different schools as a child, as his family moved between Britain and Ireland – was an unskilled manual worker. And I didn’t attend the kind of school that sent people to university.

Mine was a purpose-built comprehensive school for boys in South London. At the time its most famous alumnus (as if anyone would ever have used that term!) was Brian Jacks, the British judo champion who was feted for his squat thrust and dipping proficiency on the BBC show Superstars. It was a big moment when he came back to visit us at school assembly!

Other alumni include the self-proclaimed gangster Dodgy Dave Courtney and ‘Handy Andy’ from the 1990s BBC programme Changing Rooms (who was in my brother’s woodwork class – and yes I did both woodwork and metal work at school, not Latin!). More recently, the Liverpool right-back Joe Gomez and the YouTuber Eman Kellam, have been the most significant products of my alma mater. It was a big school – 240 in each year group – but when I was there only a tiny fraction, not many more than 20 I’d say, got to the end of their A-Levels, and not all of those went on to university.

I took, in short, an unusual path.

The first person who suggested the possibility of university to me was a physics teacher. It was significant, I think, that he was an American, and unshackled by the same class expectations as the Music teacher who told me I would never get any qualifications. One parents’ evening, when I was 15, this physics teacher (whose name I confess I can no longer remember) made a comment in passing to my parents about what I might study at university. This was so out-of-the-blue, so unexpected, so outlandish that it still gets mentioned in family discussions. It had never occurred to anyone that I might go to university, and it was questioned as to why I would want to go: ‘What would you do with a degree?’. But the idea stuck in my head and, quite weirdly I suppose, grew stronger after I read an article about The Rolling Stones which mentioned that Mick Jagger had attended the London School of Economics (LSE). By this time, I was doing an O-Level in Economics – a subject I loved – and I thought I would like to go to the LSE too.

I never made it to the LSE, but I did get to university, enrolling at what was then called Queen Mary College in London.

As an undergraduate, I lived at home. In part, my decision was about money and a desire not to impose additional costs on my parents. Were we poor? My mum would hate me for saying we were, and I knew many others who were worse off. So, let’s just say family finances were tight. But that wasn’t the only reason I stayed at home.

As a sixth former I couldn’t conceive what going away to university might be like, and I was scared (although I would not admit that, even to myself) that I would not fit in. The image of university – and more particularly ‘student life’ – that I had gleaned from television and the ill-informed comments of family and friends was not an appealing one. It probably sounds priggish, and perhaps it was, but I didn’t want to go away just to have a good time – I wanted to go to university to succeed academically. If I was going to impose costs on my family – and by not going to work I was creating a problem – then it couldn’t be frivolous, it had to be worthwhile.

I had so little to go on in terms of making decisions about university, and the one exception that I knew about second-hand weighed heavily in my mind. The son of one of my dad’s workmates, also Irish, had gone to university a few years before. This was a big deal and often spoken of. The father was immensely proud of his son and worked a second job to help pay for his studies; the son worked too. What stuck with me was how hard on all of them it was when the son messed up his degree. I was determined not to make the same mistake. If I was going to impose a cost on my family and carry the weight of their pride (and incomprehension) then I had to succeed. It wasn’t enough just to go to university I had to be a success.

So, I lived at home to save my family any extra expense (I paid my mum a minimal rent, to keep the family finances in balance) and because I thought it would help me better concentrate on my studies.

Much of my first year at Queen Mary was thoroughly miserable. I would commute in, barely talk to anyone and return home. And home was difficult at that time. But gradually I warmed to ‘college’ or ‘school’, as my family referred to it. I met people the like of which I’d never known before, including the son of a lecturer who taught at the fabled LSE! But, without any conscious choice, the people I felt closest to were those from a similar(ish) background to me: a former dockyard worker, five or six years older than me, who had returned to study; and the son of a nurse and car factory worker from Coventry. Both were working class and second-generation Irish.

Of the more obviously middle-class people I mixed with almost all shared the same left-leaning politics, and I would loudly and boorishly proclaim my class background and notice how uneasy it made them feel. It is not flattering to admit but there was more than a bit of me that felt superior about what I saw as their poverty tourism. And in seminars I was usually the most committed of students, and frequently annoyed that others did not seem to take their studies seriously or realise how fortunate they were to have opportunities that so many of my (more talented) school friends never had.

Studying in London meant I never had to mask my accent, although it did begin to soften imperceptibly, and, more broadly, I found Queen Mary unusually accepting of working-class students. Many of the History lecturers were from a different world – one in which men wore cravats and bow ties – but it did not seem to matter. Queen Mary in those days (I think some of this character has now been lost) not only sat on the Mile End Road but was also somehow rooted in the culture of the area. In the Politics department – I did a joint degree – there was a lecturer, Bill Fishman, who was straight out of the old East End and had been present, he told us, at the Battle of Cable Street. His ‘Politics and Society of East London’ course was a joy, and I remember proudly telling my dad about the essay I had written on Irish immigrants to London, and him responding with stories of his own childhood.

After I’d finished my degree, I had no real idea of what would come next. I didn’t attend my graduation; I couldn’t imagine feeling comfortable dressing up in robes and the rest of it. I thought I would get a job, but jobs were thin on the ground in 1990, and I spent most of the next year on Income Support (when that benefit still existed!), apart from a short stint working as a postman (which I did enjoy). Then, with the help of the staff at Queen Mary, I applied for and got a place to study for a PhD at Cambridge, and a whole new chapter, and set of class challenges, began.

David Stack teaches in the Department of History at the University of Reading.

This article was written for the “Celebrating Class” blog series, exhibition and conference. You can join the conversation on our Padlet.

You must be logged in to post a comment.