As part of the University’s Centenary Celebrations, a team led by David Stack in History has been researching the experiences of students and staff from working-class backgrounds at the University of Reading. Beginning with the widening participation roots of the University in the 1890s Oxford Extension movement and coming right up to date with policy recommendations for a more socially inclusive campus, the team have aimed to highlight working-class presence, celebrate success, and acknowledge ongoing challenges. Over the next few weeks, we are going to publish a series of linked blogs exploring some of the themes the team have been working on. Today, Amy Longmuir explores working-class stories in the University of Reading Special Collections.

Archives are always a treasure trove of people, events and organisations that surprise you. The University’s Special Collections and MERL Library are no exception, and it was a privilege to read the stories – public and personal – of working-class staff and students from the past century.

The university, or ‘Oxford Extension College’, was founded in 1892, and offered modules that could be studied independently of full enrolment. While the cost remained prohibitive for most working-class people, the flexibility afforded some in Reading the opportunity to study a mixture of technical and vocational courses. This novel approach created a class-diverse cohort which was at odds with the elite makeup of other established universities.

Community organisations adjacent to the University played a crucial role in expanding the availability of higher education. The Workers’ Educational Association were determined to make university education accessible for working people. From the early 1910s up to the 1970s, the WEA organised and coordinated lectures and modules that anyone from the local area could participate in. This was in keeping with the University’s original aim of ‘widening participation’ beyond wealthy elites. I believe we can learn from the tremendous impact that results from collaborating with local organisations, and through their initiative, breaking down the barriers to education that remain all too familiar today.

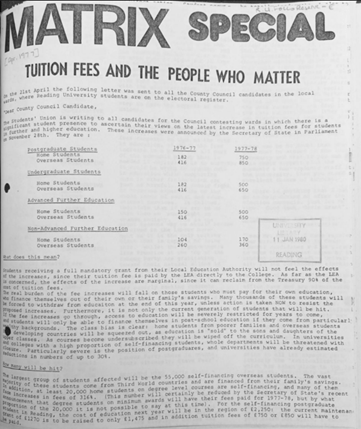

The University’s various periodicals and magazines gave insight into the lived experiences of working-class people as they entered higher education in greater numbers. Staff journals highlighted the experiences of the professional technicians who supported the running of the university. The presence (or lack thereof) of working-class people who remained in academia to work as teachers and subject experts in academic is less a matter of record. The student newspaper Matrix showed a strong reaction to tuition fee changes and the damaging impact they would have on working-class and international students.

It is striking how these narratives continue into the present day. It has been illuminating to see how some of this archival research intersects with what we learned from Sharla’s interviews with current working-class staff and students at the university. Hopefully, our research can showcase just how diverse and extensive working-class engagement with the University has been and continues to be, not only in its student population, but among staff as well.

I would like to convey my deepest thanks to the staff at Special Collections and the MERL Library for their continued support and advice on the collections they hold and how they could be useful to this project. I would particularly like to thank the Reading Room staff for their never waiving support and ability to make the archive accessible, even to a seemingly never-ending list of questions.

Amy Longmuir is an AHRC-funded PhD student in the Department of History at the University of Reading.

This article was written for the “Celebrating Class” blog series, exhibition and conference. You can join the conversation on our Padlet.

You must be logged in to post a comment.