As part of their project working with the Royal Berkshire Archive (RBA) for the module HS2GPP: Going Public, Part 2 undergraduate students Becky Storey and Eleanor Davis examined an 18th century cookbook. Read about the mysteries they uncovered below…

Early modern recipe (‘receipt’) books provide fantastic insight into the real, personal lives of our ancestors. From household management logs and home care instructions to dinner recipes and medical advice, a recipe book had it all.

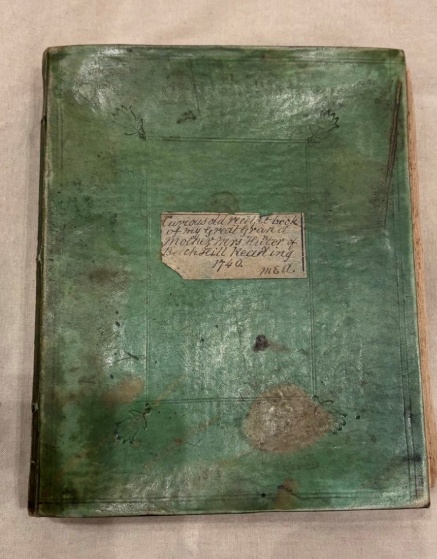

The Royal Berkshire Archives recently acquired a mysterious cookbook written in the 18th century (D/EZ224/1) that provides some insight into our local history through the eyes of an anonymous writer. This manuscript, coupled with the owner’s family archives (D/EHR), paints a picture of nobility, life, and power in Georgian Berkshire. Through a series of seasonal blogs using recipes taken from this book, starting with a wintery recipe, we hope to give you all a glimpse into the Georgian kitchen.

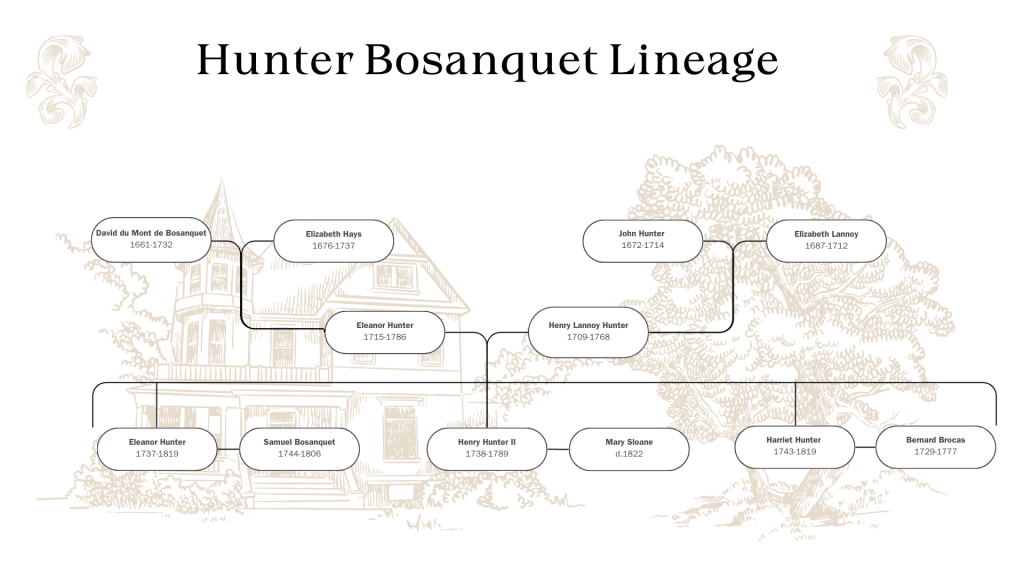

Our book is labelled ‘Curious old receipt book of my Great Grand Mother Mrs Hunter of Beech Hill, Reading’ signed by ‘MEA’. We believe MEA to be Maria Eleanor Anderdon (1819-1904), pointing to Mary Hunter (née Sloane) (1749-1822) as the original owner. However, its pages pose just as many questions as they answer. Given the timeline, the book is too old to have belonged to Maria’s great-grandmother, suggesting that the original Mrs Hunter is Eleanor Hunter (née Bosanquet) (1715-1786), or perhaps eventually her daughter, Eleanor Bosanquet (née Hunter) (1746-1819) – which is exactly as complicated as it sounds. This would fit with much of the book, but not all of it, having been written between the late 1730s and early 1750s, though many pages are undated.

Eleanor Hunter (nee Bosanquet)

Eleanor Bosanquet was born to a prominent French family in London on October 24th in 1715. The Bosanquet family were successful Merchants working with the Levant Company, operating primarily in London and in Aleppo. It is likely through these ties that Eleanor met Henry Lannoy Hunter, whom she married on June 23rd, 1736. Henry’s mother was also a French settler in London.

In 1743, Henry Lannoy Hunter Esquire purchased Beech Hill House, within the 18th-century parish of Stratfield Saye. Henry owned land across Berkshire and Hampshire, including Swallowfield, Spencer’s Wood and Mortimer. Eleanor and Henry had three surviving children: Henry, their heir, and two daughters, Eleanor and Harriet.

The Tate Gallery owns a portrait they describe as showing Henry Lannoy Hunter, a Levant Company Merchant in Aleppo, painted between 1733 and 1736. We can say with some confidence that this is an image of Eleanor Hunter’s husband.

Communal Cookery

Receipt books, as they were known, were often a communal creation, passed down through several generations within the family and to friends and neighbours. This would explain why this book, despite being attributed to the Hunter family, features more recipes by others than by Eleanor herself. The recipe book features entries by well-regarded Doctors, Lords, and Ladies, as well as local neighbours and friends. Some entries can even be traced to nearly identical recipes published in other contemporary works. The number of contributions by notable people secures the Hunter family’s position as a key part of Berkshire’s history, both through personal connections and the ability to access and read their works.

Warfield

Another mystery, however, presents itself in the book’s first few pages. Several early pages describe household information for ‘Haly’, likely referring to Hailey Green Farmhouse, in Warfield. However, there is no evidence of the Hunter family having ties to Warfield, suggesting this book has changed hands and parishes over the years. We do have some evidence that points to the prominent Neville family of Warfield working in Aleppo as Merchants, so perhaps all roads lead to Aleppo.

Enfield

Four of the recipes in the book are noted as originating in Enfield, which raises questions about the Hunter-Bosanquet family’s connections to the area and presented an opportunity to prove if this was Eleanor’s book after all. Branches of the Bosanquet family have been a prominent presence in the Early Modern County of Middlesex and North London for centuries. Records reveal that Bosanquet’s lived in mansions and manor houses in the area during the 18th century, including Broxbournebury Manor and Clay Hill Lodge, giving us a clear link to both Enfield and the Hunter-Bosanquet line.

Notable Names

The book’s outsourced recipes also add another layer of complexity. Eleanor Hunter’s book features two recipes by Lady Harriet Cholmondeley, a noblewoman who wasn’t born until 4 years after Eleanor had died. This suggests that the book has been passed down through generations, perhaps lending some validity to its original curious label, despite the intergenerational confusion. What we can confirm, based on handwriting evidence, is that more than one person contributed to this book, suggesting it wasn’t just Eleanor Hunter’s (senior) book after all.

What this tells us is that this recipe book was much like the well-loved folders, binders, and notebooks many of us have in our kitchens today, built from recipes cut from newspapers and magazines and passed between friends and family, well-used and well-loved.

– EEH

Our final mystery lies at the end of our Winter Cheese Recipe with the signature, ‘EEH’. As far as our records show, none of our Eleanors have middle names, and to add fuel to the fire, Eleanor’s Mother’s name was Elizabeth Hays. Why would a person sign off a recipe in their own book? The plot thickens. This recipe will be explored in our next post.

This blog was originally published on the RBA site, here.

You must be logged in to post a comment.