Dr Jacqui Turner explores the darker side of the divisive romantic celebration…

Our association with Valentine’s Day is one of love and romance; however, considering St Valentine’s own grisly end, it is worth exploring a darker side, including some traditions you may want to avoid!

When we think of St Valentine, it is little wonder that there is a darker side to the day, considering the various accounts of his terrible end. St Valentine was, in turn, an early Christian priest in Rome who married young men to their lovers (such as soldiers) who had been forbidden from marriage, for which he was tortured and beheaded outside the Flaminian Gate in Rome on 14th February 269. Alternatively, he was either a Christian martyr who helped Christians escape their Roman prisons, or his legend comes from the fact that he supposedly wrote a love letter shortly before his execution to the daughter of his jailer. However, the association of the Feast of Valentine’s with love first appears in the medieval period, circa 1415, when the Duke of Orleans wrote to his wife from the Tower of London, referencing Valentine. Any which way, there is no definitive account of what happened to Valentine, but his legend still inspires millions to send red roses and greeting cards. Romantics in the UK are expected to outspend other European countries, with an expected £2.3 billion in 2026. That is approximately £52 per person!

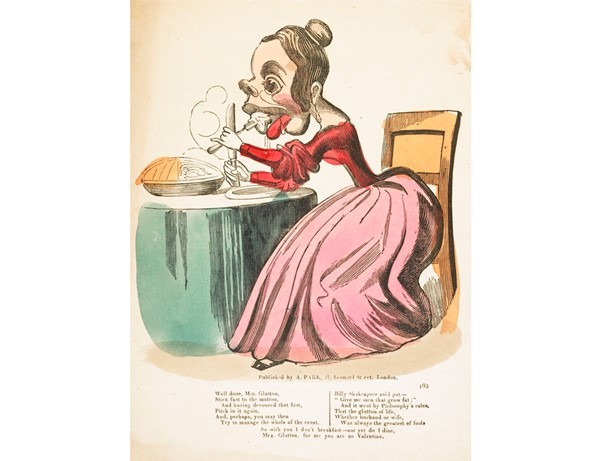

It wouldn’t be possible to discuss Valentine’s Day without broaching the subject of cards. That said, at the end of the nineteenth century, not all cards were as you might expect. The Victorians adopted the American tradition for cruel or spiteful ‘vinegar valentine’ cards, which were cheaper and less ornate than their romantic counterparts. They included caricatures of women with mocking sentiments that most often related to a woman’s appearance or less-than-feminine characteristics. This type of card was first popularised in the USA in the early 1840s, and its popularity quickly spread, becoming fashionable in Britain during the Victorian period.

The sending of greeting cards was popularised and made more widely available by new forms of mass-print production, which lowered costs. There were also improving literacy rates, and the introduction of the affordable Penny Post in 1840 reduced the cost of sending these scurrilous missives, heralding the mass sending of letters and parcels across the board. These cards were cheaper and lower in quality than romantic Valentine cards. They were printed on one side and lacked the ornate decorations of lovers’ cards. Romantic cards were often individual and handmade. The major commercialisation of Valentine cards began with Hallmark around 1905.

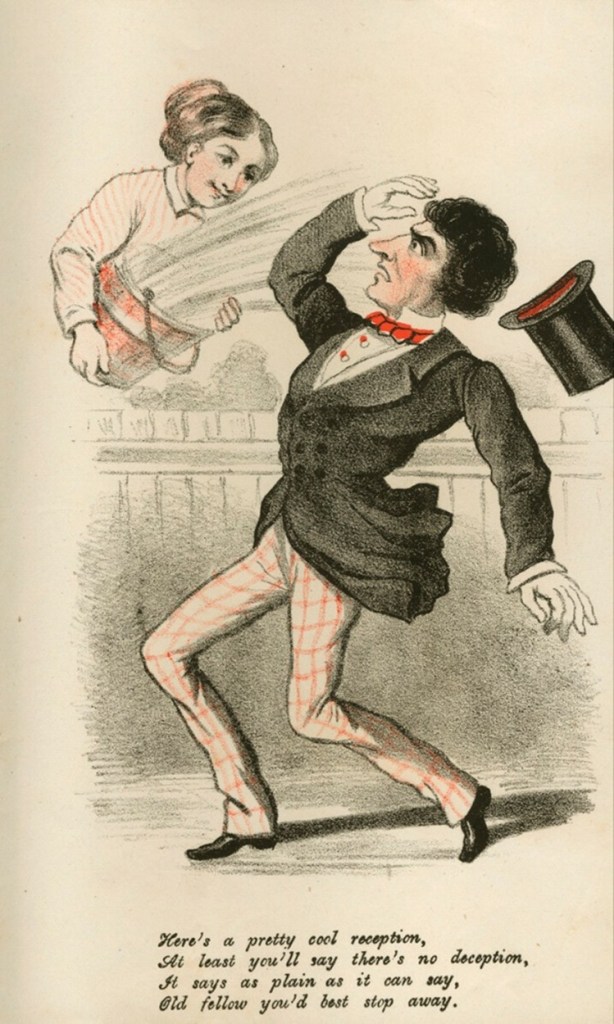

Men were not exempt from receiving a rude or an insulting vinegar valentine card either. Drunks, poor or idle servants and emasculated men were taunted in the quest of mean-spirited humour. They were also useful for getting rid of an unwanted suitor!

At least you’ll say there’s no deception,

It says as plain as it can say,

Old fellow you’d best stop away.”

© Royal Pavilion & Museums, Brighton & Hove

Vinegar valentine cards were a symptom of underlying gender anxieties that reflected wider concerns about a shift in social expectations and the accelerating pace of change, including the growing demand for women’s rights and education. They also reflected concerns regarding the changing process of courtship and expectations of marriage; an increasing demand for companionate marriage and ideas of romantic love rather than the desire to make a ‘good match’. ‘Love’ was a radical notion, as it could not be controlled; you couldn’t help who you fell in love with.

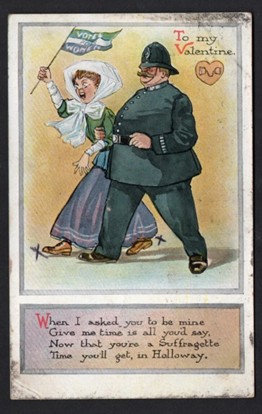

Women who stepped outside their expected gender roles were pilloried and represented. Educated women or ‘bluestockings’ regularly found themselves as the subject of these cards or in receipt of them. They were often depicted as spinsterish women who had been unable to secure a husband and had turned to education, ultimately joining the suffrage movement when all else was lost and their femininity lost through aging. Their appearances are masculine; they are sharp-tongued, and they are portrayed as desiring to emasculate men. This reached its head with the suffrage movement’s demands for equality, especially the suffragettes – women who challenged the role and parameters society had deemed fit for them. Suffragettes also became a common subject of cards. Here is one which I must admit I originally found on eBay!

Give me time is all you’d say,

Now that you’re a Suffragette,

Time you’ll get, in Holloway.”

University of Northern Iowa.

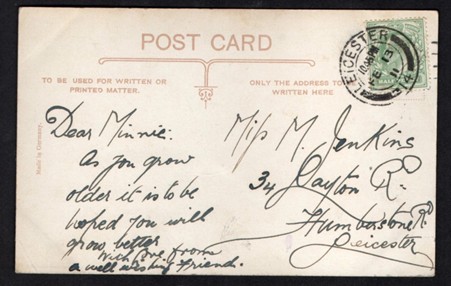

At the worst, vinegar cards were akin to modern-day trolling – though a very different format! The cheaper postal service meant that they could be sent anonymously, just like their romantic counterparts, to their unfortunate recipient. The fashion for vinegar valentines was at its height in the Victorian period, but soon clashed with Victorian morality, and the claim that these spiteful cards began to overshadow the real meaning of Valentine’s Day. You can still buy vintage vinegar valentine cards today so beware!

As you grow older it is to be hoped you will grow better

With love from a well wishing friend.” Reverse of the above.

How you sign off your card and what we give as traditional gifts matter too. It is believed that an X, as a symbol of kisses at the end of a card, reflects a time when people could not read or write and signed their names with a cross, even on legal documents such as marriage certificates. Richard Cadbury produced the first box of Valentine-themed chocolates in the mid-1800s, around 1861. The boxes were romantic works of art and, like today, cost a little more than during other times of the year! Red roses reflect the popular language of flowers; for the shy amongst us, just the sight of a bouquet of red roses speaks of love without having to say it out loud or come up with the right written expression.

It may not be surprising that while cards from a true love or fancy boxes that once contained chocolates survive in personal collections, vinegar valentines tended to be disposed of pretty sharpish!

You can find out more in the BBC Freethinking podcast, Glasgow Women’s Library, Historic UK, and through collections at Royal Pavilion and Museums, Brighton and Hove. See also: Annabella Pollen, ‘”The Valentine has fallen upon evil days”: Mocking Victorian valentines and the ambivalent laughter of the carnivalesque’, Early Popular Visual Culture, special issue: Social Control and Early Visual Culture, Volume 12, Issue, 2, 2014, pp. 127-173

You must be logged in to post a comment.