by Prof Kate Williams

Christmas Pudding is when the British Christmas dinner becomes theatre – as the pudding is brought in, drenched in brandy and set alight – and the diners dive in to find the silver sixpence…

But Christmas Pudding as we know it is a Victorian innovation – like so many of our Christmas traditions! As our wonderful pudding recipe from Eliza Acton shows (below).

Eliza Acton, ‘Chapter 21. Baked Puddings’, Modern Cookery for Private Families (1868).

For at least 200 years, our beloved British dish was merely a traditional winter pudding, filling and full of fruit that could be preserved for winter – but the Victorians turned it into a Christmas tradition and added the fashion of putting in a sixpence. Long before the Victorians made it part of the meal, it was first known as Plum Porridge, then Plum pudding. Yet it never contained a single plum.

The Beginnings

Dried fruit was used in winter cookery long before medieval times – for it both preserved meat and fish, and added sweetness more cheaply than honey. Although dried fruit was part of most celebratory winter stews and pies, we can locate the origins of pudding in ‘frumenty’, a soup or porridge made from meat, wine and spices with currants. We find this in medieval cookbooks but it may date back much earlier – and although it was popular throughout the winter months, it was always associated with Yuletide celebrations.

By the late Elizabethan period, frumenty was gradually becoming more pudding-like. The mixtures to include eggs, breadcrumbs and – most importantly – sugar, as it became cheaper thanks to discoveries in the New World. Thanks to the prunes, it became known as plum porridge. Indeed, prunes were so fashionable that any dish containing dried fruits was known as a ‘plum’ dish. It grew in popularity – but when Oliver Cromwell and the Puritans banned Christmas, the pudding fell out of fashion.

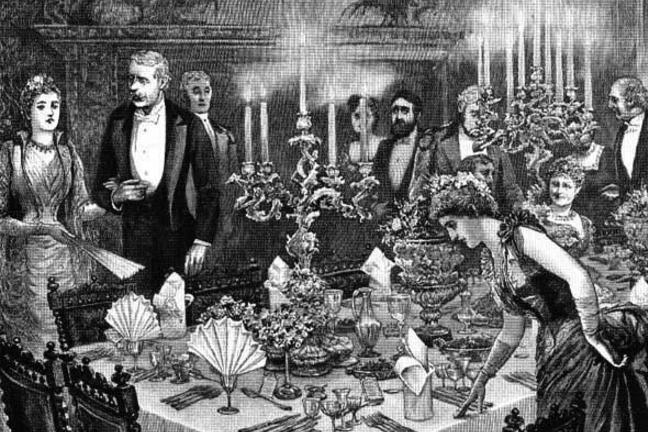

Dining à la Russe (1870), The History of Royal Food and Feasting MOOC.

Cheap sugar truly arrived in the eighteenth century – thanks to Caribbean production and the slavery against which the abolitionists fought. With the abundance of sugar, there was less need for spices and the old dishes of mixed up fruit and meat were replaced with a movement towards a division between savoury and sweet dishes. Perhaps more influential than this change was the movement in high houses from serving ‘a la Francaise’, where all the dishes were placed on the table at once, to ‘a la Russe’, with set courses. So the old plum porridge became a sweet dish – but as puddings as we know them became more fashionable, so the recipe was slowly given a more solid density.

One of the earliest plum porridge recipes is given by Mary Kettilby in her 1714 A Collection of above Three Hundred Receipts in Cookery, Physick and Surgery

One of the last recipes for Christmas plum porridge was in the cookery writing of Hannah Glass in 1747. By 1806, Maria Rundell was writing of ‘common plum pudding’, a pudding with fruit and wine.

Plum pudding lasted as a general ‘party dish’ for some time. William IV gave a feast to 3,000 poor people on his birthday in 1830, offering boiled and roast beef and ‘plum pudding’. But before long this dish would be taken up by the highest in the land.

The Victorian Christmas Pudding

The Victorian period saw the beginnings of Christmas as a great family celebration. The first to call our beloved dessert Christmas Pudding was Eliza Acton in 1845 in her brilliant Modern Cookery for Private Families of 1845.

The craze for Christmas began in 1848, when a picture of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert next to a Christmas tree was published in the Illustrated London News. But pudding passion was already going strong.

Dicken’s Ghost of Christmas Present with a Plum Pudding, University of Leeds Special Collections.

Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol (1843) portrayed the Cratchit family as ready for the thrill of the Christmas pudding:

‘In half a minute Mrs Cratchit entered: flushed, but smiling proudly: with the pudding, like a speckled cannon-ball, so hard and firm, blazing in half of half-a-quartern of ignited brandy, and belight with Christmas holly stuck into the top.

Oh, a wonderful pudding! Bob Cratchit said, and calmly too, that he regarded it as the greatest success achieved by Mrs Cratchit since their marriage.’

The traditional Plum Pudding was now shaped as a ball and called Christmas Pudding. Victoria and Albert enthroned the Christmas pudding as part of the Christmas day celebrations – painstakingly cooked by her Swiss chef, Gabriel Tschumi.

‘Oh, a wonderful pudding!’ (1905), The Victorian Web.

As the Illustrated London News declared in 1850: ‘The Plum pudding is a national symbol – It does not represent a class or caste, but the bulk of the English nation’.

Victorian Christmas pudding from the Illustrated London News (December 1848), The History of Royal Food and Feasting MOOC.

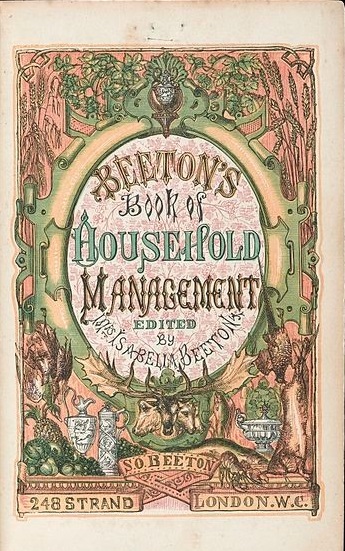

The early plum pudding was cooked – as Mrs Cratchit did – in a pudding cloth. Many Victorians experimented by putting the mixture in a basin or mould and then steaming it – allowing them to create various shapes. The Victorians were fond of designing elaborate food for festivals – weddings, funerals, Christmas – and it became fashionable to put puddings into jelly moulds. In 1861, Mrs Beeton created a Christmas pudding that looked rather like a small castle.

Mrs Beeton’s Book of Household Management (1861).

Adding holly to the pudding was a reminder of Jesus’s crown of thorns – as well as being a traditional Christmas decoration.

Adding trinkets to the pudding appears to go back to the Twelfth Night Cake which was eaten on Twelfth Night, a tradition that goes back to the fourteenth century. A dried bean or pea was baked into the cake and whoever found it was the king or queen for the night. The Victorians put in trinkets or coins instead, such as a farthing or a penny – in the twentieth century became a threepenny bit and then a sixpence – with the promise that it would bring you riches for the year. Other trinkets had various meanings – for example, a thimble meant that if a single woman found it, she would be a spinster for the rest of the year.

-

Victorian sixpence (1853), British Museum 1854,1223.13.

Other superstitions included that every member of the family should take turns to stir the pudding from east to west to remember the Wise men, or that puddings should use thirteen ingredients to reflect Jesus and his Disciples. The Sunday before Advent was always seen as ‘stir up Sunday’, with every member of the home stirring up the bowl and making a wish as they did so.

Lighting the Christmas Pudding.

Christmas Pudding is one of our most beloved traditions – the part of our Christmas meal that roots us most strongly in the past. Yet we owe so much of it to more recent times than we would imagine – and so much more to the traditions of even earlier times…

If you would like to have a go at making your own Victorian plum pudding, then why not have a look at the following recipe from Eliza Acton’s Modern Cookery (1845):

Leave a comment