by Melanie Khuddro

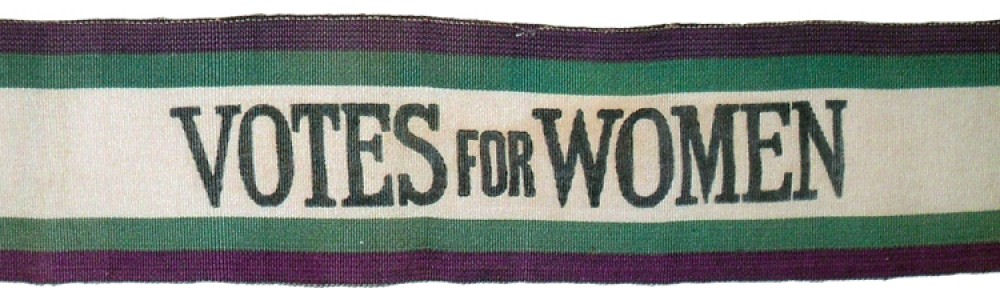

This week marks the centenary of the Representation of the People Act receiving Royal Assent; the week when women were first legally recognised to have voting rights in the UK. Countless flags, banners and badges adorned in green, white and purple have emerged at the many events and campaigns launched in celebration of the success of the suffrage movement. Inevitably, social media has monopolised the conversation with a stream of reminders that people in history fought hard to give women the political status they enjoy today, and stressing why it is important that women exercise their vote.

At a time when political apathy is at its peak (with the exception of a certain recent, single-policy issue), the power of a single vote has never succumbed to so much scrutiny. An expression of disengagement I can sympathise with. That is not to say I entirely agree with the ‘opt out’ tactic – but that is a topic for another day. Whatever your position on Blank Voting, an informed indifference is not the same as considering the political arena to be entirely beyond your remit.

On the anniversary of partial enfranchisement, I am interested in how this critique of the electorate has been burdened so specifically on the shoulders of the female constituent. Women are certainly still under-represented in political affairs and endorsing more gender diversity in the Houses of Parliament is a cause to be actively pursued. I am a keen supporter of bettering political education for younger generations and recognising the trials of early suffragists. But, with risk of further gendered isolation, I fail to see any merit in encouraging a woman to engage on the basis of other women struggling for their right to do so. Surely, that dejects the integrity of her independent authority? Would it not vindicate her right to vote to encourage her based on an ability to exercise power rather than the emotional weight of a historical martyr?

If current voting patterns reveal any kind of political alienation in a demographic, it is the underclass that we should turn our attention to. According to research conducted by Ipsos MORI, gender variance in the turnout of last year’s election was no greater than 3% for any given social class. Regardless of economic characterisations, men and women saw a total turnout gap of 2%. As much as that 2% swings in the favour of the male electorate, it does little to camouflage the chasm between the 69% of AB votes next to the 53% of DE voters.[*] *

As momentous as the passing of the Representation of the People Act was for women’s rights and the rights of working class men, it had its shortcomings, and in this centenary year there is a collective tendency to romanticise history to the point of erasing them. Among the welcomed cheers of justice for women should emerge the acknowledgement that other groups were actively excluded. Fundamentally class-driven, the Act only invited some women to participate in the vote, conditional being over the age of 30, of a high social stratum and with a property qualification for which the majority of new female voters relied on a male partnership. It excluded not only younger women but often widows over 30 who would have otherwise qualified had their husbands been alive. This piece of legislation should be celebrated as a success story in the break-down of culturally defined barriers and the liberation of a group of historically repressed people; a venture we are still in the process of achieving universally. If our dialogue is too contextual, we risk undermining its extension to other forms of social justice.

__________________________________________

__________________________________________

Header/Footer: ‘Votes for Women’ sash via Kate Willoughby, ‘#VotingMatters’, 2018, Kate Willoughby (accessed 5th February 2018).

[*] Refers to demographics classified by the National Readership Survey. The AB populace is characterised by ‘Higher-Intermediate managerial, administrative and professionals’. DE is collectively considered to be ‘semi-skilled and unskilled manual workers’ and ‘state pensioners, casual and lowest grade workers, unemployed with state benefits only’. (See nrs.co.uk for more details on socio-economic grading).

Leave a comment