by Dr Richard Blakemore [1]

Samuel Pepys, the famous diarist of the mid-seventeenth century, enjoyed Christmas (as we learned in the third post of our Christmas 2016 series). In 1661 he recorded spending a merry evening with friends; five years later, he wrote that he and his household ‘dined well on some good ribbs of beef roasted and mince pies’ – and he also mentioned that his wife Elizabeth and their servants had ‘sat up till 4’ the previous morning, making these pies.

Pepys: a fan of Christmas

Not everyone in the early modern world, however, had such a good holiday season. In those years Pepys was a rising star in the administration of the royal navy, and life for the sailors aboard the navy’s ships was tough. While Pepys caroused that Christmas Day in 1661, Edward Barlow, a mariner whose detailed and illustrated journal has survived, spent the day aboard the Martaine Galley, a navy ship which was then at Cadiz. It was, he wrote later, ‘the first Christmas that ever I had out of England, but not the last by a great many’. He was less than positive about the memory:

We had but little Christmas cheer, not having Christmas pie or roast beef … the poorest people in all England would have a bit of something that was good on such a day, and … many beggars would fare much better than we did … we [did not have] two or three days to play in and go where we would, as the worst of servants had in England, but as soon as we had ate our large dinner, which was done at three or four mouthfuls, we must work all the day afterward, and maybe a great part of the night.

The main purpose of the voyage that took Barlow away from all the festive cheer was to protect British trading interests. These contrasting Christmases therefore fit into the larger picture of the global trading networks which transformed the early modern world, and which also brought to Britain many of the things that we now associate with Christmas festivities.

Pleased to meet you Mr Strickland: a wild turkey (male), Meleagris gallopavo

Turkeys, for example, were introduced to Europe from the Americas during this period. They were supposedly first brought to England in 1526 by William Strickland, a trader from Yorkshire. Although we lack firm proof that he is responsible for their arrival, Strickland certainly added a turkey to his coat of arms in 1550; but it would take longer for them to become established as holiday fare, since Barlow’s and Pepys’s accounts suggest a rather different menu a hundred years later.

Ships trading in the East (1614)

Trade also brought more sweet and spicy tastes. Chocolate, like turkey, travelled to Europe from South and Central America, where cacao beans had long been consumed by Aztecs and Mayans – though chocolate as a liqueur did not appear until the eighteenth century, or chocolate bars until the nineteenth. The growth of trading networks also impacted on older treats, like mince pies and gingerbread, which have their origins in the medieval period. Though spices like ginger were not a new flavouring, they became steadily more plentiful once European merchants began sending their ships directly to the Indian Ocean and Southeast Asia, and Barlow himself sailed several times to India, Indonesia, and China during the course of his seafaring life.

Baking gingerbread, lebküchner, (1520)

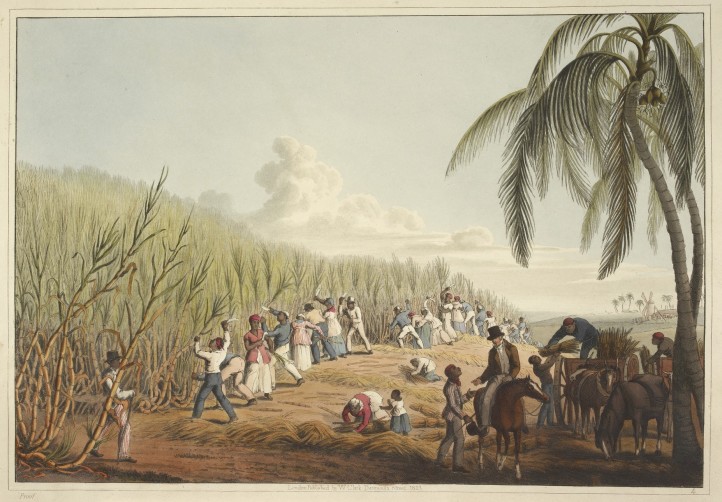

Sugar was another old sweetener that became more accessible during this period, and the history of both sugar and spices have their less palatable side. The Dutch East India Company seized much of Indonesia (including the ‘Spice Islands’, today called the Maluku Islands), imposing a harsh rule and importing slaves to maximise their trading profits. Sugar plantations in the medieval Mediterranean had also used slave labour, and this model was exported and massively expanded into the Atlantic from the fifteenth century onwards – first to islands off the coast of Africa, then to Brazil, the Caribbean, and North America. Demand for sugar, and for the labour to produce it, contributed to the transatlantic slave trade: around two-thirds of the African captives shipped across the Atlantic Ocean were taken to the Caribbean and Brazil, where sugar was the most important crop.

The other side of European trade: the sugar plantations (1823)

Barlow and Pepys probably did not think much about these global changes on Christmas Day in 1661, but their lives were deeply bound up in them. As you indulge your sweet tooth over the holiday period, perhaps take a moment to consider where all these commodities come from, and how much the early modern desire for exotic treats changed our world. [2]

Do you fancy baking your own historical gingerbread? If so why not have a look at the following recipe published in Maria Rundell’s early nineteenth-century New System of Cookery:

Our recipes come courtesy of the FutureLearn MOOC (Massive Online Open Course) ‘A History of Royal Food and Feasting’, which has been created by the University of Reading and Historic Royal Palaces. Our particular thanks to HRP’s food historian Annie Grey (for her research into these historic recipes).

__________________________

Leave a comment